[Images: Cacti at the Huntington Library in Pasadena].

[Images: Cacti at the Huntington Library in Pasadena].My wife and I went out to the Huntington's Desert Garden yesterday. I have to admit to a certain wild amount of enthusiasm for high-end botanical environments like that.

Being a fan of Kew Gardens, for instance, or Longwood Gardens, or even small local greenhouses and the like, I have a huge soft-spot for regions of the Earth's surface that have been deliberately cultivated to support rare – or at least highly condition-dependent – plantlife.

In the case of Kew and Longwood, you walk through elaborate, mist-filled greenhouses, passing orchids and ferns – but the word greenhouse is actually a form of structural shorthand, saying, in fact, that architecture has been put to use in the evolutionary hybridization of plantlife: flowers, fruits, and other animate forms that would, naturally, have grown elsewhere.

By establishing micro-climates, with often extreme variation from building to building, in both temperature and humidity, architecture participates directly in botanical speciation.

[Image: Cacti at the Huntington Library in Pasadena].

[Image: Cacti at the Huntington Library in Pasadena].In any case, these thoughts don't actually apply to the Huntington Desert Garden, which is entirely outdoors – or, at least, the part of it that we visited was entirely outdoors, in the dry heat of a spectacular, arm-sunburning day – but no matter: either way, it's hard to have a bad time walking around in the Huntington's linked network of curved paths past biomorphically avant-garde cacti and spiked trees so surreal they appear literally extraterrestrial.

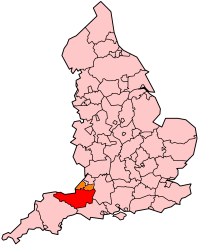

Briefly, all of this reminds me of an incredible fact I read last week in the London Review of Books: Stefan Buczacki, the author of Garden Natural History, has "calculate[d] that private gardens [in England] occupy an area about the size of Somerset, and they play an important part in maintaining the populations of many species."

[Image: Somerset County, England].

[Image: Somerset County, England].That is to say: an area in England the size of Somerset is actually a kind of biological transplant: a deliberately cultivated micro-climate, or genetic testing site, with its own yet to be calculated effects both on native plants and animals and on the British climate.

At what point, then, do privately held and cultivated landscapes become naturalized as a region's terrain, or as part of that region's native biosphere?

It's a surrogate, or prosthetic, ecosystem – a kind of skin graft – masquerading as the thing that's been replaced.

Think of it as the English family garden as replicant.

In other words, if English private gardens proliferate to the point where an area not just the size of Somerset County, but of, say, Somerset, Wiltshire, and Gloucestershire combined, then do artificial landscapes become indicative of England itself?

Or, to use an absurd analogy, if the band Napalm Death now has no connection to the original band – because all of the original members have left – indeed, as Wikipedia points out, "by the second side of their debut album... they did not contain any original members" – is it possible that, in a thousand years' time, or in five thousand years' time – or even in fifty – that "England" will soon be England in name only, having been slowly replaced, piece by piece – a garden here, a garden there – until the Britannic landscape is entirely manmade and it's become impossible to locate even a trace of native vegetation? A kind of ecological bait-and-switch?

You book a trip to England – but you're visiting an island made entirely from private gardens, a vast, unnatural landscape ruled over by a King.

In any case, the Huntington Desert Garden is a spectacular place to visit, and as good a place as any in which to think about the local cultivation of non-native landscapes. So if you're ever in Los Angeles, consider stopping by.

(Earlier on BLDGBLOG: Kew Brew, or: turning endangered landscapes into beer).

No comments:

Post a Comment