[Image: The cast of Sunshine; courtesy of DNA Films].

[Image: The cast of Sunshine; courtesy of DNA Films].I saw Sunshine the other day, so I thought I'd offer a few thoughts about it here. However, please beware that this post gives away key plot details and spoils the end of the film – so do not read this post if you'd like to avoid such knowledge.

In brief, myself and two friends went to see the film together – and we had three totally different reactions. One of us was basically annoyed with it from the very beginning – and a weird plot twist, that I'll soon discuss, about 5/6ths of the way through the movie, just killed it for him; the other more or less liked everything about the film, even accepting said "weird plot twist" for interesting reasons of his own; and I really liked the film, with several reservations, until, yes, the aforementioned weird plot twist – which basically does the whole thing in for me. In fact, I'm still stunned that this one particular detail ever made it into the script.

In any case, what the film does – and it does this very successfully, in my opinion – is set up an increasingly melancholy sense of psychological isolation as an international crew of scientists, aboard a ship called the Icarus 2, flies toward the Sun. The Sun, we learn, is dying – and so it needs to be restarted with a "stellar bomb" the size of Manhattan. In fact, we learn, the bomb is so big that it contains literally all of the Earth's fissile material. Once detonated, it will form "a star within a star" – a surrogate astronomy, or Sun-replacement surgery, that will save everyone back on Earth from the perpetual winter in which they've been trapped.

Whether or not this would actually work, from the standpoint of an astral physicist, is beside the point; you're asked to accept this, as the basic plot of the film, and, as far as that goes, I accepted it.

Meanwhile, the visual and conceptual beauty of certain scenes – they witness a transit of Mercury, for instance – is extraordinary. Further, the possibility that they may not make it back to Earth, though still unlikely at the film's beginning, adds a distinct aura of extinction and exclusivity to everything they see.

No one will ever see these things again.

[Images: Screen-grabs from the Sunshine website; courtesy of DNA Films].

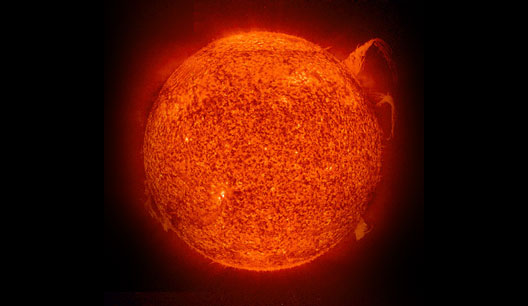

[Images: Screen-grabs from the Sunshine website; courtesy of DNA Films].However, as the ship approaches its solar rendezvous, a kind of elemental, alien hostility begins to emerge – not from within the crew members, but from within the Sun itself. Far from being a beneficent source of light in the sky, generously tanning the bodies of we Earthlings below, the Sun is revealed as a monstrous and abiological source of mutative radiation, inhumanly immense, so bright you can't see it, disintegrating nearly everything that comes near.

One of the crewmembers – the resident psychiatrist – becomes addicted to the star: he can't stop burning himself with more and more quantities of sunlight, asking the ship's central computer to increase the unfiltered percentage that is allowed through the observation deck window. With his skin peeling and his mouth hanging open, he nearly disappears into a void made entirely of light – golden, enveloping him on all sides – yet we hear, incredibly, that he's only receiving 3.1% of the Sun's natural capacity. 4%, we're told, would destroy the psychiatrist outright – let alone 50% or 90%, or the Sun itself, unfiltered.

In fact, for me, the film very brilliantly illustrates the paradox that something can be so powerful that the ability to experience it is simply beyond the limits of human life – outside of human experience altogether.

[Image: The sun].

[Image: The sun].Anyway, if the first 4/5ths or even 5/6ths of the film are about this painfully beautiful, almost evaporative, encounter with an alien and threateningly vast – yet so ironically necessary to life on Earth – stellar object, then the "weird plot twist" that I mentioned above feels as if the ending to another film had been accidentally stitched on in the editing room.

In brief: Sunshine suddenly turns into The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

[Image: The ship from Sunshine; courtesy of DNA Films].

[Image: The ship from Sunshine; courtesy of DNA Films].It's as if the film shies away from its own material, unable, or unwilling, to contemplate what might happen if people, aware of their own impending deaths, fly straight into the Sun – an origin point devoid of recognizability – and so they throw a serial killer in, almost literally out of nowhere.

The film could have been stunning: the crew is pared down, one by one, by accidents or oxygen shortages, and even a suicide, until only three or four of them are left. They know that they will never return; they know that they will die unprecedented deaths, obliterated by Apollo, by God, by the Sun – by whatever you want to call it; and they are terrified by that rapturous undoing, unable to narrate their final experience for anyone back home, truly cut off yet almost psychedelically alive in this moment of solar contact...

But that's not how the film ends.

[Image: The flight deck from Sunshine, in a screen-grab from the film's website; courtesy of DNA Films].

[Image: The flight deck from Sunshine, in a screen-grab from the film's website; courtesy of DNA Films].Midway through Sunshine, a distress beacon is heard. It's from the mission before their mission – the one that failed. That ship – called Icarus 1 – disappeared nearly seven years ago, somewhere in the irradiated gulf between Mercury and the Sun.

In a decision that, I'll concede, is necessary for certain things to come but is still so ridiculous as to make viewers question the competence of the entire crew – the last great hope of humanity! – they decide to deviate their mission in order to find the lost ship.

Lo! They find the lost ship.

Lo! They know exactly how to dock with it, despite – for obvious reasons – never having practiced anything of the sort.

Lo! Unbeknownst to them, the captain of the Icarus 1 is still alive – and he hides out on the Icarus 2, escaping notice. Like a comic book superhero, he's survived seven years alone on a disabled spaceship floating between Mercury and the Sun – without being pulled in by that star's gravity. As if serving simply to make the film's existential themes explicit, he has also pre-recorded an angry and completely unhinged theological rant about God's Will and the absurdity of Man trying to restart the Sun.

Even more unbelievably, it turns out that this guy isn't malnourished, semi-skeletal, or even psychologically catatonic: no, after seven years alone, eating hydroponic carrots in space, he's become a superstrong, sunburnt Hercules, capable of lifting two crewmembers at a time with one arm whilst chasing everyone else down and murdering them with a mechanized surgical scalpel.

[Images: Two views of the airlock from Sunshine, in screen-grabs from the film's website; courtesy of DNA Films].

[Images: Two views of the airlock from Sunshine, in screen-grabs from the film's website; courtesy of DNA Films].Where did this come from?

And why?

At the risk of wildly exaggerrating the philosophical depth of the first 5/6ths of the film, this seems roughly akin to throwing in a serial killer for the last three chapters of Thus Spoke Zarathustra – Nietzsche is chased through the claustrophobic rooms of his mountain home – or adding the Son of Sam to the grand finale of the Tao Te Ching.

In any case, can you really be so scared of your own premise – the unwitnessed and lonely deaths of an oxygen-starved crew as they fly into the Sun, toting a "stellar bomb" the size of Manhattan (talk about mythological plotlines!) – that you have to add Freddy Krueger?

Even worse, the film had already established by then that no one would survive. The film had already established that the Sun was a source of great attractive power, far beyond the mere pull of gravity, and that it was possible to become hypnotized by, even addicted, to the very thing that would later annihilate you – and that this death would be more horrible than human pain can describe, yet something of such exquisite agony, and so spectacular, something uniquely sublime in the history of human experience, that you would actually want to feel it.

You would fall toward roiling continents of hydrogen and light, and you would be utterly consumed by your destination.

It would have been the science fiction film of the decade! An instant classic.

Instead, just when everyone has settled in for the ending, waiting for that golden burn, our mutant Hercules of unlimited arm strength appears, creeping up behind people in the dark and knifing them in the spine.

How could you cheat the audience and the characters out of the philosophical glory of solar absorption? Sunshine would practically have been a religious text, a near classic work of speculative philosophy exploring what it means not just to die but to be completely obliterated, atomically consumed in chemical radiance by the same two-faced point of origin that makes life on Earth possible in the first place.

Imagine if the Chandogya Upanishad ended not with the nature of time, space, life, and astronomy – but with an ax murderer.

Or Siddhartha: the Buddha is inexplicably hunted by an escaped convict with a chainsaw... (That sounds kind of fun, actually).

Does this mean that I am comparing the film Sunshine to the Chandogya Upanisad? Well... I suppose I am, out of over-enthusiasm – but I am also saying that Sunshine wildly misses that mark. Instead of going for cinematic magnificence, and it was well on its way to arriving there, it takes a disastrous step back – and reveals itself as a cheap, quasi-1990s space-horror misfire.

Was the knife-wielding lunatic evidence of tampering by the studio? In other words, did the film's producers demand more of a predictable impact? Or did Alex Garland write that guy into the original script? If so, why? Were the filmmakers pleased with the final result? Were they so unhappy with the idea of flying their own crew into the Sun that they added an interstellar He-Man, sunburnt and stronger than Arnold Schwarzeneggar?

Or was the knife-wielding lunatic a way to screen the filmmakers themselves from the imaginative power of their own subject matter?

Was there something about the premise itself – total absorption by a featureless, golden void – that forced them to retreat, and to insert something that they and, they hoped, the audience could recognize?

[Image: Cillian Murphy runs from a knife-wielding, sunburnt lunatic in Sunshine, a screen-grab from the film's website; courtesy of DNA Films].

[Image: Cillian Murphy runs from a knife-wielding, sunburnt lunatic in Sunshine, a screen-grab from the film's website; courtesy of DNA Films].Like I say, if the film hadn't already been on its way to the final credits, with no need for such a plot twist, I could perhaps have accepted the chromosomally damaged avenger. If it had been the ship's resident psychiatrist, for instance, psychotically consumed by the Apollonian power of astral radiance, at least it would have been neat and tidy – if still clichéd.

But since we were already on our way into the Sun, already past the point of even thinking that the crew might return home, already accepting the fact that everyone in the film would die heroic, astronomically unprecedented deaths, why did we need the murderous accelerant of a Sun-addled stowaway?

That does nothing more than rob the film of its poetic grandeur – so that the filmmakers could safely turn their back on philosophy and create Leviathan in zero-G.

(Thanks to Christopher and Michael for seeing the film with me – and for listening to me rant about all of the above for nearly two hours. Meanwhile, if you completely disagree with this review, please jump in and convince me otherwise. Earlier on BLDGBLOG: The Oxygen Garden).

No comments:

Post a Comment