[Image: This post was originally published last winter in Blend, translated into Dutch].

[Image: This post was originally published last winter in Blend, translated into Dutch].Last winter

The New York Times reported on a surprising growth industry in the United States: the physical relocation of old houses.

This is the somewhat surreal activity of transporting entire, intact buildings from one place to another, often over more than one hundred miles.

A single-family home, for instance, will be "jacked up" – like a car with a flat tire – so that "long steel beams" can be inserted between the house and its foundations. Very slowly, the house is then disconnected from the surface of the earth and loaded onto the back of a lorry.

If you think that sounds easy, however, bear in mind that some houses "have to be broken into two or more pieces" during this process and the roofs must often be removed. Removing the roofs streamlines the structures for highway transport, allowing them "to pass under power lines, bridges and trees" as they make their way to a new location. After all, as one whole house relocation client jokes: "The last thing you want is to show up one morning and find they’ve lopped off a room during the night."

[Image: Photo by Stewart Cairns for The New York Times].

[Image: Photo by Stewart Cairns for The New York Times].Transporting an intact house along the American interstate highway system can take several days. Worse, it can "cost hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars." One such relocation job was so complex, the article explains, that it "required the bulldozing of a temporary access road," and that was simply to remove the structure from its original plot of land.

But, even then, the troubles aren’t over.

After a house has been installed on its new foundation, it might need to be re-assembled – and this means "putting the house back together from thousands of pieces" while carefully following page after page of engineering notes, photographs, drawings, and detailed architectural plans so that you don’t put anything back in the wrong place.

[Image: Photo by James Edward Bates for The New York Times].

[Image: Photo by James Edward Bates for The New York Times].My first thought when I read this was of all those dinosaur skeletons now standing silently in museums around the world. What if someone, somewhere, got something wrong? What if they used the wrong skull on the wrong spine – or they attached the wrong leg, the wrong jawbone – and so the whole bodily form needs to put together again, perhaps with pieces from other dinosaurs in other museums far away?

Because what if your house gets moved three hundred miles but the bedroom is inadvertently attached to the wrong floor? Or two entire houses get mixed up along the way – what strange new architectural styles might result?

These are more than rhetorical questions.

Just last week, for instance, Christopher Hawthorne wrote a short article for the

L.A. Times about a single family house that

literally crashed onto the side of a freeway in Los Angeles.

[Image: Photo-illustration by Aaron Goodman for the L.A. Times].

[Image: Photo-illustration by Aaron Goodman for the L.A. Times].Soon known as the Freeway House, "the single-story structure had been on its way from Santa Monica to Santa Clarita a few weeks ago, riding atop a trailer, when it smashed into an overpass and came to rest on the shoulder of the 101 in the Cahuenga Pass."

It then just sat there.

For 10 days.

[Image: Photo by John Fuentes, found via the L.A. Times].

[Image: Photo by John Fuentes, found via the L.A. Times].It was an uncannily accurate, if entirely unintentional, comment on life in today's Los Angeles: a house stranded on the side of a freeway, with no context or human history in sight.

But what, I might ask, would have happened if the Freeway House had not crashed into a bridge but

into another tractor trailer, carrying another house, and those two structures had then merged – even if only temporarily, in mid-air, a kind of post-deconstructive act of architecture lasting mere milliseconds in a cloud of debris above the L.A. freeway system – and then a third building, and a fourth...?

Soon architecture schools are teaching their students as much about car crashes as they are about CAD.

In this context, perhaps

the crash could be a future strategy for architectural design: load the Taj Mahal, the Vatican, something by Mies, and an entire American suburb onto three dozen lorries, then crash them all together on a remote German autobahn. Photograph the results.

J.G. Ballard would be proud.

In any case, the whole-house relocation industry would have it so much easier if residential structures were built to move in the first place. The internal structure of a building could incorporate wheels, pulleys, gears, and other machine parts, thus allowing the house to be reconfigured, even geographically relocated. A building could simply attach itself to the local railroad tracks and slip away…

You report your house missing – but Interpol soon finds it: its windows have been smashed and it's covered in graffiti, and it's sitting next to a road outside Thessaloniki.

It misses you.

[Image: Corb v2.0 by Andrew Maynard].

[Image: Corb v2.0 by Andrew Maynard].With these thoughts in mind, then, I got an email from Australian architect

Andrew Maynard announcing a new project that he and his office had just finished putting together.

Maynard’s

Corb v2.0 is a speculative housing complex that serves to update Le Corbusier’s old idea of the house as “a machine for living in” – and Maynard takes that statement to its logical extreme.

He proposes permanently incorporating a cargo container-stacking machine into a new residential suburb. The machine would thus rearrange all the houses on a near-continual basis.

[Images: Two views of Corb v2.0 by Andrew Maynard].

[Images: Two views of Corb v2.0 by Andrew Maynard].If a family doesn’t like where their home is located, they simply wait another day: “Yesterday this was a penthouse apartment on the other end of the complex,” Maynard explains. “Today the family has returned to find it on the ground floor.”

You can move up, down, left, right – even turn 180º around and face the other direction. You see sunset instead of sunrise, or a forest instead of a lake.

[Images: Three more views of Corb v2.0 by Andrew Maynard].

[Images: Three more views of Corb v2.0 by Andrew Maynard].As Maynard describes it, this gigantic, crane-like stacking machine would smoothly glide back and forth over lines of “movable housing modules.” Residents could wake up to find themselves elsewhere, perhaps closer to the parking lot; neighbors would always have new neighbors.

This way, “everyone gets a penthouse as often as they get a ground level apartment” – which has the effect of “transforming traditional real estate valuations.”

[Image: Corb v2.0 by Andrew Maynard].

[Image: Corb v2.0 by Andrew Maynard].Taking this yet further, though, I'd suggest that we need more than isolated clusters of container-homes, each connected to one stacking machine. We need thousands of these things, aligned in continuous routes like train tracks, connecting neighborhoods, cities, countries, and continents. A house in the U.S. soon shows up in Mexico; a house in Utrecht moves to Sri Lanka. Immigration laws are rewritten, with complex architectural sub-rules. Customs officials the world over are required to take summer classes at

SCI-Arc. Criminal homeowners shift back and forth across the International Date Line, avoiding taxes – while astronauts look down at great crowds of houses: whole cities migrating in a web across the earth.

Every once in a while, though, kicking off new schools of architectural thought and theory, there is a

Great Accident. Architects stop reading

Paul Virilio to concentrate on derailing entire cities...

(For more Andrew Maynard on BLDGBLOG see Unhinged and treeborne. For more posts that originally appeared in Blend, meanwhile, don't miss Fossil Rivers, The Weather Emperors, Urban Knot Theory, Abstract Geology, Wreck-diving London, and The Helicopter Archipelago).

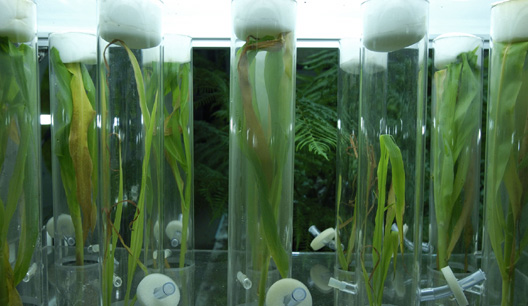

[Image: Bel-Air by Mathieu Lehanneur].

[Image: Bel-Air by Mathieu Lehanneur]. [Image: Bel-Air by Mathieu Lehanneur].

[Image: Bel-Air by Mathieu Lehanneur].

[Images: The Oxygen Garden from Sunshine, courtesy of DNA Films].

[Images: The Oxygen Garden from Sunshine, courtesy of DNA Films].

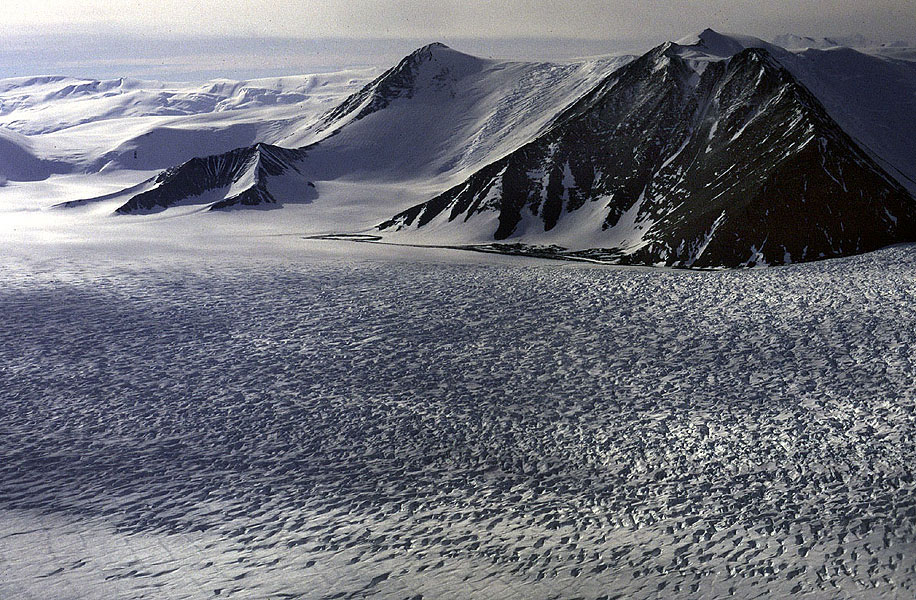

[Image: The IceCube's surface workings, Antarctica; via

[Image: The IceCube's surface workings, Antarctica; via  [Image: A schematic diagram of the

[Image: A schematic diagram of the  [Image: A glimpse of the Transantarctic Range].

[Image: A glimpse of the Transantarctic Range].

[Image: Algae balloon communities in Iceland by the Philadelphia-based

[Image: Algae balloon communities in Iceland by the Philadelphia-based  [Image: Algae balloons and the houses they serve, by the

[Image: Algae balloons and the houses they serve, by the  [Image: An Icelandic hydrogen economy, outlined by the

[Image: An Icelandic hydrogen economy, outlined by the  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: A broader view of the plan by the

[Image: A broader view of the plan by the

[Image: Boutique Monaco by

[Image: Boutique Monaco by

[Images: Three rendered views of the building's lobby and ground level exterior].

[Images: Three rendered views of the building's lobby and ground level exterior].

[Images: Day and night renders of the project's exterior, complete with punctuated vertical bays of greenery and residential terracing; view both the

[Images: Day and night renders of the project's exterior, complete with punctuated vertical bays of greenery and residential terracing; view both the  [Image: A kind of rooftop park and bioscape, complete with what appears to be a helipad].

[Image: A kind of rooftop park and bioscape, complete with what appears to be a helipad]. [Image: The Boutique Monaco under construction; view

[Image: The Boutique Monaco under construction; view  [Image: Bracing at the base of the Boutique Monaco; view

[Image: Bracing at the base of the Boutique Monaco; view

[Image: This post was originally published last winter in

[Image: This post was originally published last winter in  [Image: Photo by Stewart Cairns for

[Image: Photo by Stewart Cairns for  [Image: Photo by James Edward Bates for

[Image: Photo by James Edward Bates for  [Image: Photo-illustration by Aaron Goodman for the

[Image: Photo-illustration by Aaron Goodman for the  [Image: Photo by John Fuentes, found via the

[Image: Photo by John Fuentes, found via the  [Image:

[Image:

[Images: Two views of

[Images: Two views of

[Images: Three more views of

[Images: Three more views of  [Image:

[Image:  [Image: The solar-powered

[Image: The solar-powered  [Image: The Minimum Mobile Module by

[Image: The Minimum Mobile Module by  [Image: The Carapace House by

[Image: The Carapace House by  [Image: The Drop Off Unit by

[Image: The Drop Off Unit by  [Image: The Jellyfish House by

[Image: The Jellyfish House by