The bright young thing mentality: the penchant for fantasy and masquerade had become an expression of the disregard they felt for the immediate past or the immediate future. They lived -or tried to live - outside their time. Philip Hoare, Serious Pleasures, the life of stephen tennant

The bright young thing mentality: the penchant for fantasy and masquerade had become an expression of the disregard they felt for the immediate past or the immediate future. They lived -or tried to live - outside their time. Philip Hoare, Serious Pleasures, the life of stephen tennantArchitectural engineering design.autocad career .learnin,news,architecture design tutorial,

Wednesday, December 30, 2009

Masquerade

The bright young thing mentality: the penchant for fantasy and masquerade had become an expression of the disregard they felt for the immediate past or the immediate future. They lived -or tried to live - outside their time. Philip Hoare, Serious Pleasures, the life of stephen tennant

The bright young thing mentality: the penchant for fantasy and masquerade had become an expression of the disregard they felt for the immediate past or the immediate future. They lived -or tried to live - outside their time. Philip Hoare, Serious Pleasures, the life of stephen tennantToday's archidose #381

The Westside Sales Centre in Toronto, Ontario by Alsop Architects, 2006. Not sure if this building still stands, but according to this recent article the loft building it was designed for has "been scuppered."

To contribute your Flickr images for consideration, just:

:: Join and add photos to the archidose pool, and/or

:: Tag your photos archidose

Art Trap

[Image: From Art Trap by Minsuk Cho].

[Image: From Art Trap by Minsuk Cho].In an amazing response to the Guggenheim Museum's Contemplating the Void call-for-ideas (mentioned in the previous post), architect Minsuk Cho has proposed Art Trap.

Explaining their approach, the architects write that "the Guggenheim has become, in a sense, a victim of its own success due to an over-saturation of human movement in a singular space. Our proposal aims to accomplish the seemingly incompatible: to restore a museum environment conducive to experiencing art and to maximize and heighten other experiences brought about by the iconic status of the museum itself."

The specific strategy here is "to trap, i.e., to force a pause. This programmatic component was not considered by Wright, who envisioned a space defined by tireless motion."

[Images: From Art Trap by Minsuk Cho].

[Images: From Art Trap by Minsuk Cho].The resulting project is a gigantic membrane stretched throughout the interior, supplying "180 saddle-like seats along the entire ramp for pausing and viewing the rotunda."

- These seats protrude into the void with access ladders arranged in between the floor and the ceiling over the guardrails. Each of the 90 access ladders holds two cantilevering seats, which are angled gradually as they ascend to allow a view of the central area at ground level that functions almost like a stage—as though the rotunda were a new hybrid of opera house and arena. The 180 protrusions over the void are draped with a single, soft and translucent membrane that functions as a safety net.

[Image: From Art Trap by Minsuk Cho].

[Image: From Art Trap by Minsuk Cho].The architects continue, writing that "the pop-out pods, each approximately 60 cm deep, contain seats," and "each pod has five openings for the head and limbs, which make the membrane"—and I love this metaphor—"much like a garment that can be worn collectively by 180 people."

Imagining a piece of clothing so huge you mistake for a building is an awesome change in both scale and context; you would go inside by putting the building on, slipping in one arm at a time.

Of course, this also raises the possibility of tailoring clothing specifically to function only within certain very specific architectural structures: nylon tights that only make sense to wear when seated in one of Cho's "pop-out pods," or sweaters that allow you to experience the spatial extravagance of luxury elevators at a new W Hotel in London. You and some friends zip yourselves up into the wall, forming a new private room that would otherwise not be there.

[Images: From Art Trap by Minsuk Cho].

[Images: From Art Trap by Minsuk Cho].But Cho saves the best analogy for last: once the overflowing crowds of art-drunk tourists come to fill the "pop-out pods," it "as if they were performing as a part of a living Baroque ceiling sculpture."

[Image: From Art Trap by Minsuk Cho].

[Image: From Art Trap by Minsuk Cho].I had the pleasure of seeing Cho present this project in person at a lecture he gave back in October at Columbia University; this was the project with which he kicked-off the evening, and it set a fantastically giddy tone for the rest of Mass Studies' work.

You can see this and other projects at the forthcoming Contemplating the Void exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum, opening February 12, 2010.

Spiral Icon

[Image: Flow Show by WORKac (2009)].

[Image: Flow Show by WORKac (2009)].For a forthcoming exhibition called Contemplating the Void, New York's Guggenheim Museum "invited more than two hundred artists, architects, and designers to imagine their dream interventions in the space."

- In this exhibition of ideal projects, certain themes emerge, including the return to nature in its primordial state, the desire to climb the building, the interplay of light and space, the interest in diaphanous effects as a counterpoint to the concrete structure, and the impact of sound on the environment.

[Image: Untitled by N55 (2009)].

[Image: Untitled by N55 (2009)].The interior is taken over by coastal rain forests; there are mystical arabesques of colored music wrapping upward in spatially impossible curls through the museum's disappeared roof; there are trampolines and climbing nets strung from wall to wall above the lobby.

The Museum of Simulated Suicides, you could call it, where go to experience what it might be like to throw themselves into the void. You get a certificate of survival at the end.

[Images: (top) Let's Jump! by MVRDV (2009) and (bottom) Experiencing the Void by Julien De Smedt Architects (2009), the latter project also depicted in Agenda, pubished earlier this month].

[Images: (top) Let's Jump! by MVRDV (2009) and (bottom) Experiencing the Void by Julien De Smedt Architects (2009), the latter project also depicted in Agenda, pubished earlier this month].There are photo-collages and sectional diagrams of internally returning ecosystems.

[Images: (top) Morris in Guggenheim by M/M (2009), (center) Perfection_Perversion by West 8 (2009), and (bottom) The House of GI–A Proposal by Matthew Ritchie (2009)].

[Images: (top) Morris in Guggenheim by M/M (2009), (center) Perfection_Perversion by West 8 (2009), and (bottom) The House of GI–A Proposal by Matthew Ritchie (2009)].There are vast white balloons with visible structures trapped inside them rising out into New York's winter skies—

[Image: State Fair Guggenheim by MAD Architects (2009)].

[Image: State Fair Guggenheim by MAD Architects (2009)].—as well as storms of red dust falling downward in a kind of gravitational pollution of the lobby.

[Image: Untitled by Anish Kapoor (2009)].

[Image: Untitled by Anish Kapoor (2009)].Perhaps predictably, though, I might say an even better intervention into the Guggenheim's space is not a series of objects or architectural alterations at all, but an event—by which I'm specifically referring to one of 2009's most talked-about spatial moments, at least in architectural circles, when we see that very same museum annihilated in a hail of bullets in the film The International.

[Image: A poster for The International featuring the Guggenheim Museum (2009)].

[Image: A poster for The International featuring the Guggenheim Museum (2009)].For all these calls for ideas and architectural design competitions, what if Hollywood set designers and location scouts are doing a more provocative job in non-preciously reimagining the inherited icons of the global built environment than 21st century architects?

These and many other images will be on display when the exhibition, Contemplating the Void, opens February 12, 2010.

Tuesday, December 29, 2009

A modern renovation

Featured in the March 2008 issue of Metropolitan Home magazine was an example of a city apartment with great bones which was renovated efficiently and beautifully. The great bones were there, natural light, outdoor space and tall ceilings on a high floor.

Featured in the March 2008 issue of Metropolitan Home magazine was an example of a city apartment with great bones which was renovated efficiently and beautifully. The great bones were there, natural light, outdoor space and tall ceilings on a high floor. Jeffrey Povero, an architect in NYC, renovated the space for himself and his partner in a 1914 hospital buiding which had been converted to apartments in the 80s. The space was a bland box when he found it, but he saw promise in the 11 foot ceilings and views of the brooklyn bridge. I'm sure the huge terrace and three exposures didn't hurt either!

Jeffrey Povero, an architect in NYC, renovated the space for himself and his partner in a 1914 hospital buiding which had been converted to apartments in the 80s. The space was a bland box when he found it, but he saw promise in the 11 foot ceilings and views of the brooklyn bridge. I'm sure the huge terrace and three exposures didn't hurt either! What started out as plans for minimal renovations turned into a gut job, as these types of jobs often do. Why do anything half way? While not a small apartment by New York standards at 860 SF, it still had to operate efficiently for the two.

What started out as plans for minimal renovations turned into a gut job, as these types of jobs often do. Why do anything half way? While not a small apartment by New York standards at 860 SF, it still had to operate efficiently for the two. I would buy a rat filled shoebox of an apartment for that terrace. Amazing! I'm in love with the walnut paneling Povero had installed behind the fireplace (top image) and in the kitchen below and with the acres of white marble. I would have used a beefier countertop at the island though I think.....it looks fragile and skimpy.

I would buy a rat filled shoebox of an apartment for that terrace. Amazing! I'm in love with the walnut paneling Povero had installed behind the fireplace (top image) and in the kitchen below and with the acres of white marble. I would have used a beefier countertop at the island though I think.....it looks fragile and skimpy. Povero wanted to create a modern men's club, which I think reads very strongly. While a bit minimal for my personal tastes, I think the apartment is stunning.

Povero wanted to create a modern men's club, which I think reads very strongly. While a bit minimal for my personal tastes, I think the apartment is stunning. One thing Povero and I share is a love of organization, although he takes it further than I; his books, seen above, are arranged in Dewey Decimal order! He worked for years at Robert Stern designing libraries: I suppose that will do it for you!

One thing Povero and I share is a love of organization, although he takes it further than I; his books, seen above, are arranged in Dewey Decimal order! He worked for years at Robert Stern designing libraries: I suppose that will do it for you!

Mirrors were used in the apartment advantageously to reflect the light and views and make small rooms feel bigger. The photo below looks like 2 rooms almost!

The closet is also a work of supreme organization. How many closets get published in magazines? I drooled over this.....

The closet is also a work of supreme organization. How many closets get published in magazines? I drooled over this.....

The closet is also a work of supreme organization. How many closets get published in magazines? I drooled over this.....

The closet is also a work of supreme organization. How many closets get published in magazines? I drooled over this.....

Even if it's not your style, I think everyone can appreciate the work that went into this space!

photographs by Peter Murdock

New Camera

The sad news is that my old camera (2002 canon powershot sds) finally died yesterday and I'm in the market for a new one. The good news is that I get to take advantage of updated technologies, mainly size! My old camera was small for the time (basically pocketsize) and has performed really well, but as the years progressed smaller versions were being released. As I like to carry my camera around with me all the time, size is so important -it must fit in my pocket!

The sad news is that my old camera (2002 canon powershot sds) finally died yesterday and I'm in the market for a new one. The good news is that I get to take advantage of updated technologies, mainly size! My old camera was small for the time (basically pocketsize) and has performed really well, but as the years progressed smaller versions were being released. As I like to carry my camera around with me all the time, size is so important -it must fit in my pocket!

I'm thinking of replacing it with the same model, unless anyone has any other suggestions, the Canon PowerShot SD780 IS. Is anyone familiar with this version of camera?

It also comes in 4 colors and I'm having a difficult time deciding which I want to go with . I value your opinion: what color would you chose? Silver, black, red or gold? I'm leaning towards gold (shown)..... and shying away from red which I feel is a target when traveling. Thoughts?

Monday, December 28, 2009

Manhattan Paleolimnology

Temporary lakes have sprung up all over Manhattan again this week, sometimes more than twenty feet wide and a foot deep, spanning curbs and pooling in gutters, the aquatic remains of last week's rain and snowmelt.

[Image: Photo by Flickr-user ShellyS].

[Image: Photo by Flickr-user ShellyS].

This surprise limnology—often demanding new, indirect lines of approach from one side of the street to the next—reminded me of David Gissen's recent, recommended book Subnature, which includes an entire chapter on urban puddles.

"Although we often think of puddles as inconsequential," Gissen writes, "they appear in architectural history in prominent ways—in drawings of ruins, photographs of decaying buildings, and experimental designs that attempt to use water in provocative ways." Now, however, "these stagnant pools of water, once signifying society's vulnerabilities, appear to have disappeared in much contemporary work"; indeed, he adds, contemporary architects have seemingly always "viewed stagnant water with suspicion." There is good medical reason for this suspicion, of course; indeed, the Centers for Disease Control advised last year that "neglected swimming pools"—i.e. stagnant bodies of water—are fast becoming vectors for mosquito-borne disease.

The CDC specifically cites "the adjustable rate mortgage and associated housing crises" as unexpected disease incubators: "Associated with home abandonment was the expanding number of neglected swimming pools, jacuzzis (hot tubs), and ornamental ponds. As chemicals deteriorated, invasive algal blooms created green swimming pools that were exploited rapidly by urban mosquitoes, thereby establishing a myriad of larval habitats within suburban neighborhoods," they wrote.

In any case, Gissen describes "visions of the undrainable city" as a kind of sickly counterpart to the modern, infrastructurally managed, rational metropolis, pointing out that "the waters inundating the modern city rained from above and surged from below." These overload our modern streets and sewers, bringing even 21st-century cities closer to the flooded Roman basements of Piranesi than to the hygienic visions of Le Corbusier, Gissen suggests. I'm reminded here of a disconcerting remark made by Alan Weisman in The World Without Us that the subways of New York City would be irreparably flooded within only 36 hours if the city's underground pumps ceased to function.

While reading Gissen's chapter on puddles, however, one of the first things that came to mind is that someone should produce a puddle map of New York—an urban atlas of temporary flooding. Set your parameters—puddles one foot deep by thirty-feet wide, say, or, more accurately, a volumetric guideline (at least one hundred square-feet of water or no less than 120 gallons)—and bring these fleeting aqueous forms into the geographic consciousness of the city.

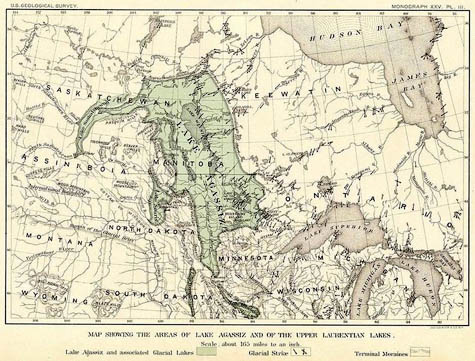

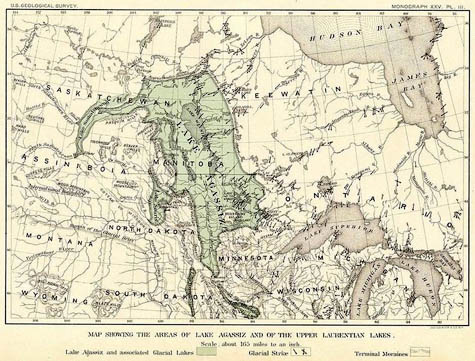

[Image: A map of glacial Lake Agassiz].

[Image: A map of glacial Lake Agassiz].

From one rainy season to the next, an accelerated paleolimnology of New York thus comes into being; the Lake Lahontans and Lake Agassizs of the five boroughs are given their cartographic due. Here a tiny lake once stood, historical plaques could read, bringing to mind a liquid version of Taylor Square, the famed "smallest park" in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

What monstrous puddles have existed in your neighborhood, and how have the urban circumstances of their existence changed over time? Did curb-cuts or new drains eliminate these hydro-geographies—or even make them worse? And whose lives have been affected by these unmapped bodies of water, whether through hydroplaning, sidewalk splashes, or even an expensive pair of ruined shoes?

Whole personal histories of human contact with puddles, and the effects such exposure might have, could be produced or recorded. This is extraordinary: we live beside temporary lakes and inland seas in cities all over the planet, yet these landmarks never make it onto our maps.

[Image: Photo by Flickr-user ShellyS].

[Image: Photo by Flickr-user ShellyS].This surprise limnology—often demanding new, indirect lines of approach from one side of the street to the next—reminded me of David Gissen's recent, recommended book Subnature, which includes an entire chapter on urban puddles.

"Although we often think of puddles as inconsequential," Gissen writes, "they appear in architectural history in prominent ways—in drawings of ruins, photographs of decaying buildings, and experimental designs that attempt to use water in provocative ways." Now, however, "these stagnant pools of water, once signifying society's vulnerabilities, appear to have disappeared in much contemporary work"; indeed, he adds, contemporary architects have seemingly always "viewed stagnant water with suspicion." There is good medical reason for this suspicion, of course; indeed, the Centers for Disease Control advised last year that "neglected swimming pools"—i.e. stagnant bodies of water—are fast becoming vectors for mosquito-borne disease.

The CDC specifically cites "the adjustable rate mortgage and associated housing crises" as unexpected disease incubators: "Associated with home abandonment was the expanding number of neglected swimming pools, jacuzzis (hot tubs), and ornamental ponds. As chemicals deteriorated, invasive algal blooms created green swimming pools that were exploited rapidly by urban mosquitoes, thereby establishing a myriad of larval habitats within suburban neighborhoods," they wrote.

In any case, Gissen describes "visions of the undrainable city" as a kind of sickly counterpart to the modern, infrastructurally managed, rational metropolis, pointing out that "the waters inundating the modern city rained from above and surged from below." These overload our modern streets and sewers, bringing even 21st-century cities closer to the flooded Roman basements of Piranesi than to the hygienic visions of Le Corbusier, Gissen suggests. I'm reminded here of a disconcerting remark made by Alan Weisman in The World Without Us that the subways of New York City would be irreparably flooded within only 36 hours if the city's underground pumps ceased to function.

While reading Gissen's chapter on puddles, however, one of the first things that came to mind is that someone should produce a puddle map of New York—an urban atlas of temporary flooding. Set your parameters—puddles one foot deep by thirty-feet wide, say, or, more accurately, a volumetric guideline (at least one hundred square-feet of water or no less than 120 gallons)—and bring these fleeting aqueous forms into the geographic consciousness of the city.

[Image: A map of glacial Lake Agassiz].

[Image: A map of glacial Lake Agassiz].From one rainy season to the next, an accelerated paleolimnology of New York thus comes into being; the Lake Lahontans and Lake Agassizs of the five boroughs are given their cartographic due. Here a tiny lake once stood, historical plaques could read, bringing to mind a liquid version of Taylor Square, the famed "smallest park" in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

What monstrous puddles have existed in your neighborhood, and how have the urban circumstances of their existence changed over time? Did curb-cuts or new drains eliminate these hydro-geographies—or even make them worse? And whose lives have been affected by these unmapped bodies of water, whether through hydroplaning, sidewalk splashes, or even an expensive pair of ruined shoes?

Whole personal histories of human contact with puddles, and the effects such exposure might have, could be produced or recorded. This is extraordinary: we live beside temporary lakes and inland seas in cities all over the planet, yet these landmarks never make it onto our maps.

Sunday, December 27, 2009

Rousseau and Echolocation

[Image: Perspective by Jan Vredeman de Vries; no explicit relation to this post].

[Image: Perspective by Jan Vredeman de Vries; no explicit relation to this post].Writing about the human experience of night before electricity, A. Roger Ekirch points out that almost all internal architectural environments took on a murky, otherworldy lack of detail after the sun had gone down. It was not uncommon to find oneself in a room that was both spatially unfamiliar and even possibly dangerous; to avoid damage to physical property as well as personal injury to oneself, several easy techniques of architectural self-location would be required.

Citing Jean-Jacques Rousseau's book Émile, Ekirch suggests that echolocation was one of the best methods: a portable, sonic tool for finding your way through unfamiliar towns or buildings. And it could all be as simple as clapping. From Émile: "You will perceive by the resonance of the place whether the area is large or small, whether you are in the middle or in a corner." You could then move about that space with a knowledge, however vague, of your surroundings, avoiding the painful edge where space gives way to object. And if you get lost, you can simply clap again.

Ekirch goes on to say, however, that "a number of ingenious techniques" were developed in a pre-electrified world for finding one's way through darkness (even across natural landscapes by night). These techniques were "no doubt passed from one generation to another," he adds, implying that there might yet be assembled a catalog of vernacular techniques for navigating darkness. It would be a fascinating thing to read.

Some of these techniques, beyond Rousseau and his clapping hands, were material; they included small signs and markers such as "a handmade notch in the wood railing leading to the second floor," allowing you to calculate how many steps lay ahead, as well as backing all furniture up against the walls at night to open clear paths of movement through the household.

Entire, community-wide children's games were also devised so that everyone growing up in a village could become intimately familiar with the local landscape.

- Games like "Round and Round the Village," popular in much of England, familiarized children at an early age to their physical surroundings, as did fishing, collecting herbs, and running errands. Schooled by adults in night's perils, children learned to negotiate the landscapes "as a rabbit knows his burrow"—careful after dark to skirt ponds, wells, and other hazardous terrain. In towns and cities, shop signs, doorways, and back alleys afforded fixed landmarks for neighborhood youths.

But this idea, so incredibly basic, that children's games could actually function as pedagogic tools—immersive geographic lessons—so that kids might learn how to prepare for the coming night, is an amazing one, and I have to wonder what games today might serve a similar function. Earthquake-preparedness drills?

In any case, we return to Rousseau. We see him advancing, now, heading forward into unknown architecture, dark space enveloping him on all sides, the walls fading into obscurity, black, leg-breaking stairwells threatening in the distance, unsure of where he stands, entirely alone in this shadow... until we hear a series of claps. And then another. Then one more.

And the philosopher, echoing himself, finding comfort and location based on objects he can't see, soon works his way out of the labyrinth.

Saturday, December 26, 2009

Today's archidose #380

Brugge Pavilion in Bruges, Belgium by Toyo Ito & Associates, Architects, 2002.

To contribute your Flickr images for consideration, just:

:: Join and add photos to the archidose pool, and/or

:: Tag your photos archidose

Friday, December 25, 2009

Recovering

Thursday, December 24, 2009

Villa Karma

One of the most beautiful early modern houses, in my opinion, is the Villa Karma by Adolf Loos (primary designer, 1904-1906 - Hugo Ehrlich finished the design). Loos is known as one of the foremost early modernists who abandoned ornament of any kind.  The Villa Karma on Switzerland's Lake Geneva was his first major project, and here he was experimenting with what modernism was and yet still referencing the classical tradition more than in his later projects. It's this juxtoposition that I love so much and yet is so hard to find.

The Villa Karma on Switzerland's Lake Geneva was his first major project, and here he was experimenting with what modernism was and yet still referencing the classical tradition more than in his later projects. It's this juxtoposition that I love so much and yet is so hard to find. Loos's life, by the way, was a veritable soap opera, that would shock the most liberal biographer today. His contemporary, Frank Lloyd Wright was a walk in the park comparitively! But I'm not here to talk about his life ( you can read about it on wikipedia HERE if you're interested). The rear of the house, which faces the lake, takes advantage of the views with steep garden terracing, huge windows and numerous outdoor rooms.

Loos's life, by the way, was a veritable soap opera, that would shock the most liberal biographer today. His contemporary, Frank Lloyd Wright was a walk in the park comparitively! But I'm not here to talk about his life ( you can read about it on wikipedia HERE if you're interested). The rear of the house, which faces the lake, takes advantage of the views with steep garden terracing, huge windows and numerous outdoor rooms. Here you can see some of the classical Doric columns that are used here on a loggia, but also at the front entrance as seen in the top image. Their presence is striking against the slick and austere facade of stucco. Notice also the statue of a face to the left - a classical element.

Here you can see some of the classical Doric columns that are used here on a loggia, but also at the front entrance as seen in the top image. Their presence is striking against the slick and austere facade of stucco. Notice also the statue of a face to the left - a classical element.

While he eschewed traditional ornament, he used beautiful materials on the interior of the house to great effect: nothing boring here. The house is a positive mausoleum of beautiful marbles. In the oval entry foyer, a pattern of black and white marble on the floor contrasts with a rosey marble used on the walls and gold tiles on the ceiling.

While he eschewed traditional ornament, he used beautiful materials on the interior of the house to great effect: nothing boring here. The house is a positive mausoleum of beautiful marbles. In the oval entry foyer, a pattern of black and white marble on the floor contrasts with a rosey marble used on the walls and gold tiles on the ceiling. The upper level of this opening, as seen from the hallway above, was an obvious precedent for Michael Grave's own house in New Jersey (as was much of the work of Loos). Recognize it?

The upper level of this opening, as seen from the hallway above, was an obvious precedent for Michael Grave's own house in New Jersey (as was much of the work of Loos). Recognize it? The library again shows the decorative (but not ornamental) use of marble and wood with large windows overlooking the lake. I could spend all day in this room!

The library again shows the decorative (but not ornamental) use of marble and wood with large windows overlooking the lake. I could spend all day in this room! This corner of the library shows another modern take on 'tradition' - a stained glass window.

This corner of the library shows another modern take on 'tradition' - a stained glass window.

The most famous room in the house, however (which also appears on the cover) is the master bathroom. Classicism rears its head again, this time in a black marble. The bronze doors are studded and I wouldn't want to walk into them in the middle of the night! The sink is between the 2 doors seen below: this room is enormous - a veritable temple to cleanliness!

The most famous room in the house, however (which also appears on the cover) is the master bathroom. Classicism rears its head again, this time in a black marble. The bronze doors are studded and I wouldn't want to walk into them in the middle of the night! The sink is between the 2 doors seen below: this room is enormous - a veritable temple to cleanliness!

The dining room again uses tons of marble, with an interesting metal ceiling. I wish I could find a color photograph of this. Do you think it's copper? Steel? While this room looks cold in this photo,I think with a tablecloth, dishes, chairs - it would warm right up. But this is definitely a cold house, probably better suited for a tropical climate rather than Switzerland!

The dining room again uses tons of marble, with an interesting metal ceiling. I wish I could find a color photograph of this. Do you think it's copper? Steel? While this room looks cold in this photo,I think with a tablecloth, dishes, chairs - it would warm right up. But this is definitely a cold house, probably better suited for a tropical climate rather than Switzerland! The loggia, off the dining room is similar in form, but the floor pattern from the dining room is echoed on the ceiling out here in a classical motif. The niches at the end of the space are also somewhat classical (and I feel were probably added by Ehrlich and not Loos)

The loggia, off the dining room is similar in form, but the floor pattern from the dining room is echoed on the ceiling out here in a classical motif. The niches at the end of the space are also somewhat classical (and I feel were probably added by Ehrlich and not Loos) The photographs are by Roberto Schezen from the marvelous book, Adolf Loos Architecture 1903-1932 by Kenneth Frampton and Joseph Rosa.

The photographs are by Roberto Schezen from the marvelous book, Adolf Loos Architecture 1903-1932 by Kenneth Frampton and Joseph Rosa.

The Villa Karma on Switzerland's Lake Geneva was his first major project, and here he was experimenting with what modernism was and yet still referencing the classical tradition more than in his later projects. It's this juxtoposition that I love so much and yet is so hard to find.

The Villa Karma on Switzerland's Lake Geneva was his first major project, and here he was experimenting with what modernism was and yet still referencing the classical tradition more than in his later projects. It's this juxtoposition that I love so much and yet is so hard to find. Loos's life, by the way, was a veritable soap opera, that would shock the most liberal biographer today. His contemporary, Frank Lloyd Wright was a walk in the park comparitively! But I'm not here to talk about his life ( you can read about it on wikipedia HERE if you're interested). The rear of the house, which faces the lake, takes advantage of the views with steep garden terracing, huge windows and numerous outdoor rooms.

Loos's life, by the way, was a veritable soap opera, that would shock the most liberal biographer today. His contemporary, Frank Lloyd Wright was a walk in the park comparitively! But I'm not here to talk about his life ( you can read about it on wikipedia HERE if you're interested). The rear of the house, which faces the lake, takes advantage of the views with steep garden terracing, huge windows and numerous outdoor rooms. Here you can see some of the classical Doric columns that are used here on a loggia, but also at the front entrance as seen in the top image. Their presence is striking against the slick and austere facade of stucco. Notice also the statue of a face to the left - a classical element.

Here you can see some of the classical Doric columns that are used here on a loggia, but also at the front entrance as seen in the top image. Their presence is striking against the slick and austere facade of stucco. Notice also the statue of a face to the left - a classical element. While he eschewed traditional ornament, he used beautiful materials on the interior of the house to great effect: nothing boring here. The house is a positive mausoleum of beautiful marbles. In the oval entry foyer, a pattern of black and white marble on the floor contrasts with a rosey marble used on the walls and gold tiles on the ceiling.

While he eschewed traditional ornament, he used beautiful materials on the interior of the house to great effect: nothing boring here. The house is a positive mausoleum of beautiful marbles. In the oval entry foyer, a pattern of black and white marble on the floor contrasts with a rosey marble used on the walls and gold tiles on the ceiling. The upper level of this opening, as seen from the hallway above, was an obvious precedent for Michael Grave's own house in New Jersey (as was much of the work of Loos). Recognize it?

The upper level of this opening, as seen from the hallway above, was an obvious precedent for Michael Grave's own house in New Jersey (as was much of the work of Loos). Recognize it? The library again shows the decorative (but not ornamental) use of marble and wood with large windows overlooking the lake. I could spend all day in this room!

The library again shows the decorative (but not ornamental) use of marble and wood with large windows overlooking the lake. I could spend all day in this room! This corner of the library shows another modern take on 'tradition' - a stained glass window.

This corner of the library shows another modern take on 'tradition' - a stained glass window. The most famous room in the house, however (which also appears on the cover) is the master bathroom. Classicism rears its head again, this time in a black marble. The bronze doors are studded and I wouldn't want to walk into them in the middle of the night! The sink is between the 2 doors seen below: this room is enormous - a veritable temple to cleanliness!

The most famous room in the house, however (which also appears on the cover) is the master bathroom. Classicism rears its head again, this time in a black marble. The bronze doors are studded and I wouldn't want to walk into them in the middle of the night! The sink is between the 2 doors seen below: this room is enormous - a veritable temple to cleanliness! The dining room again uses tons of marble, with an interesting metal ceiling. I wish I could find a color photograph of this. Do you think it's copper? Steel? While this room looks cold in this photo,I think with a tablecloth, dishes, chairs - it would warm right up. But this is definitely a cold house, probably better suited for a tropical climate rather than Switzerland!

The dining room again uses tons of marble, with an interesting metal ceiling. I wish I could find a color photograph of this. Do you think it's copper? Steel? While this room looks cold in this photo,I think with a tablecloth, dishes, chairs - it would warm right up. But this is definitely a cold house, probably better suited for a tropical climate rather than Switzerland! The loggia, off the dining room is similar in form, but the floor pattern from the dining room is echoed on the ceiling out here in a classical motif. The niches at the end of the space are also somewhat classical (and I feel were probably added by Ehrlich and not Loos)

The loggia, off the dining room is similar in form, but the floor pattern from the dining room is echoed on the ceiling out here in a classical motif. The niches at the end of the space are also somewhat classical (and I feel were probably added by Ehrlich and not Loos) The photographs are by Roberto Schezen from the marvelous book, Adolf Loos Architecture 1903-1932 by Kenneth Frampton and Joseph Rosa.

The photographs are by Roberto Schezen from the marvelous book, Adolf Loos Architecture 1903-1932 by Kenneth Frampton and Joseph Rosa.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Or fantasy could be as simple as dressing up in costume for the evening: full of high hopes for the future and escaping the past year.

Or fantasy could be as simple as dressing up in costume for the evening: full of high hopes for the future and escaping the past year.

Whatever form your fantasies take or whatever you may wear, I hope you have great New Years celebrations!

Whatever form your fantasies take or whatever you may wear, I hope you have great New Years celebrations!