[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].

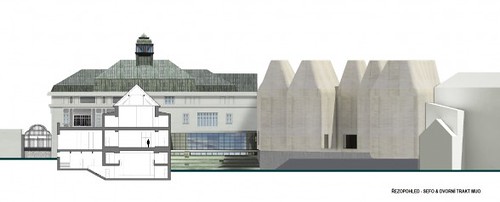

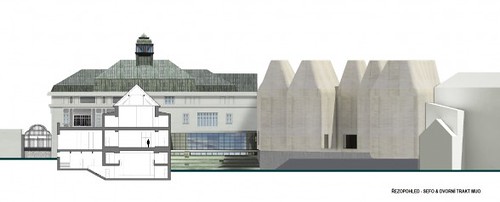

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].I'm a fan of this strangely megalithic museum and cultural center made from a series of concrete shells, colored white with crushed marble, proposed for the Czech city of Olomouc.

According to the designers,

Šépka Architekti, the project "attempts to draw inspiration from both... a small scale of mediaeval subdivision of land on the one hand and the large scale of palaces, ecclesiastical and military buildings of the

Předhradí beginning here on the other."

[Image: Sketch of the Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti, looking vaguely like an inverted, institutional-scale variation on Neil Denari's Useful and Agreeable House].

[Image: Sketch of the Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti, looking vaguely like an inverted, institutional-scale variation on Neil Denari's Useful and Agreeable House].The museum is divided into five apparently separate but linked buildings; this is due to "the necessary separation of the individual functions of the exhibition halls, library, entry hall or bookshop and refreshments," a "necessary separation" that also generates a convenient spatial identity for the overall project.

One of the coolest things about the design, though, is what Šépka Architekti call their "house in a house" idea, inspired by access to indirect sunlight: "Even in the cases when an upper floor is inserted in an individual building, daylight is ensured on the lower floor through placement of a smaller structure. We thus approach the topic of a ‘house in a house’, which ensures favourable conditions for the the display of exhibits on the walls while providing light from above on both floors."

You can see the formal implications of this in the below image, where a massive, seemingly hovering trapezoid acts both as another, elevated room for gallery use and as a massive, light-filtering device for the skylights further above.

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].It's a mass that casts shadows inside the building.

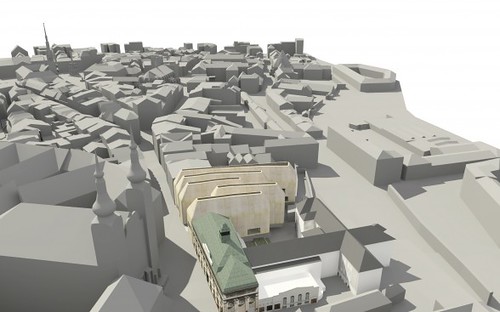

Provided the exterior concrete ages well, the museum's fivefold street presence—briefly stepping back at one point to form a public plaza—is actually pretty stunning. It manages to allude to design languages as diverse as Neo-Brutalism, the Romanesque, a kind of

Tatooine Moderne, and computer harddrive casings (although I'm reminded of Owen Hatherley's

recent quip about "a modernised classicism, monumental yet free in details, that usually gets subsumed under the meaningless retrospective coinage 'art deco'"—here, we might say, "modern geometries, imposing in size, built from concrete, and thus subsumed under the meaningless retrospective coinage 'Neo-Brutalism'").

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].The results are quite beautiful in profile, even when simply rising up behind the walls of neighboring buildings.

In any case, the interior volumes also lend themselves well to defining an overall spatial experience, even while departing from one another just enough to keep each bay or gallery distinct.

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].As mentioned earlier, that interior is a mix of art galleries, a library, a bookshop/cafe, performance spaces, and, oddly enough, as if Photoshopped in simply to prove a point, a basketball court. Note that the stadium seating visible in many of these images has been mounted on rails for ease of rearrangement.

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].

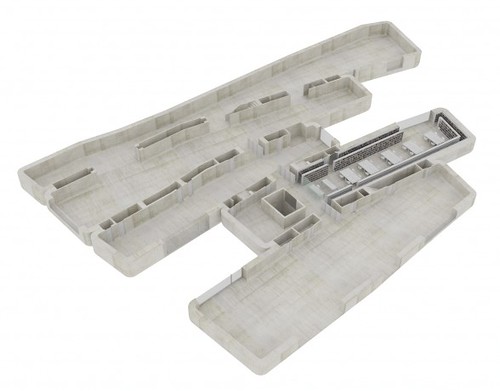

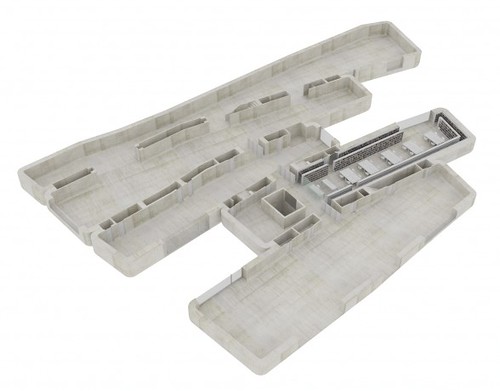

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].In plan, it's interesting to remember that the separate units of the building here were generated from what

Šépka Architekti referred to as the "small scale of mediaeval subdivision of land." In other words, the buildings take their formal cue—at least abstractly—from ancient real estate divisions on the ground in Olomouc, not from some overzealous application of the architects' own stylized form of site analysis.

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].The complete building, seen in slices:

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].

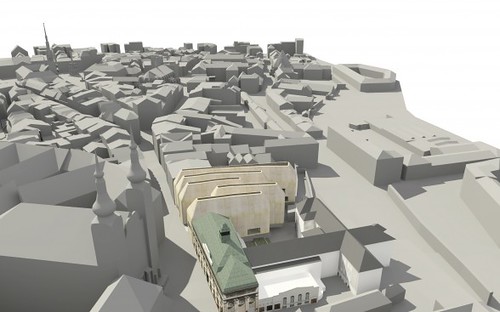

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].Further, the "small scale of mediaeval subdivision of land" that I've mentioned three times now also means that what could very easily be an imposing, alien monolith made from smooth white concrete, stuck irresponsibly in the center of the city, actually manages to be appropriate in scale.

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].

[Image: Central European Forum, Olomouc, by Šépka Architekti].The building hasn't been constructed, of course, and we have no real idea how the concrete will age; but I was struck by the images from the instant I saw them, flipping through a back issue of

a10 yesterday afternoon.

Check out more images courtesy of

Šépka Architekti.

The most magical spot at Filoli is probably the Summe House, also known as the tea house or more commonly known as a garden pavilion. Little accessory structures like this area always the jewel of any estate; Just think of the follies of English Country Homes.

The most magical spot at Filoli is probably the Summe House, also known as the tea house or more commonly known as a garden pavilion. Little accessory structures like this area always the jewel of any estate; Just think of the follies of English Country Homes. Sitting between the walled garden and the formal garden adjoining the house which I showed the other day HERE, the small structure has views from its one room of all areas of the estate: the house, the formal gardens, the pool area, the walled garden and last but not least the gorgeous mountain view.

Sitting between the walled garden and the formal garden adjoining the house which I showed the other day HERE, the small structure has views from its one room of all areas of the estate: the house, the formal gardens, the pool area, the walled garden and last but not least the gorgeous mountain view. The room is floored with 3 types of marble in a graphic grid pattern and paneled with ornate boiseries. Designed by Arthur Brown Jr., this is the same formality seen at his well known SF City Hall (which I'll post about next week) but on a MUCH smaller scale. He made elegant grandeur cozy; Just who wouldn't want to have tea here?

The room is floored with 3 types of marble in a graphic grid pattern and paneled with ornate boiseries. Designed by Arthur Brown Jr., this is the same formality seen at his well known SF City Hall (which I'll post about next week) but on a MUCH smaller scale. He made elegant grandeur cozy; Just who wouldn't want to have tea here? These lovely sconces were originally intended for the stair well in the house, but fit in nicely here too adding to the formality of the space.

These lovely sconces were originally intended for the stair well in the house, but fit in nicely here too adding to the formality of the space. This column above is a copy of the Satyr plant stand found in Pompeii and was originally in the Bourn's SF house, as was the marble table in the center of the room.

This column above is a copy of the Satyr plant stand found in Pompeii and was originally in the Bourn's SF house, as was the marble table in the center of the room. The comfortable wicker chairs and profusion of plants bring life to the space. I can imagine it being a lovely cool spot on a hot day because of all the marble. Had it been seen empty, it might appear to be a very sunny mausoleum!

The comfortable wicker chairs and profusion of plants bring life to the space. I can imagine it being a lovely cool spot on a hot day because of all the marble. Had it been seen empty, it might appear to be a very sunny mausoleum! Some closeups of the very elegant woodwork. Someone worked very hard getting everything to meet JUST SO.

Some closeups of the very elegant woodwork. Someone worked very hard getting everything to meet JUST SO. You can't miss the summer house in the gardens and before our guide took us in, I think every person in the group managed to ask if we would see inside! Tomorrow -more of the gardens.

You can't miss the summer house in the gardens and before our guide took us in, I think every person in the group managed to ask if we would see inside! Tomorrow -more of the gardens.

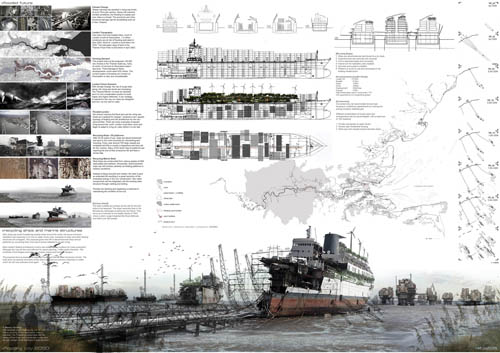

[Image: From "

[Image: From "

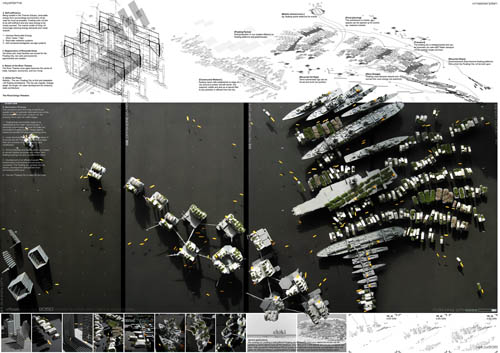

[Images: From "

[Images: From "

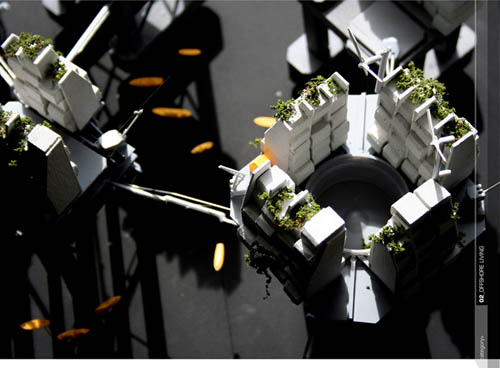

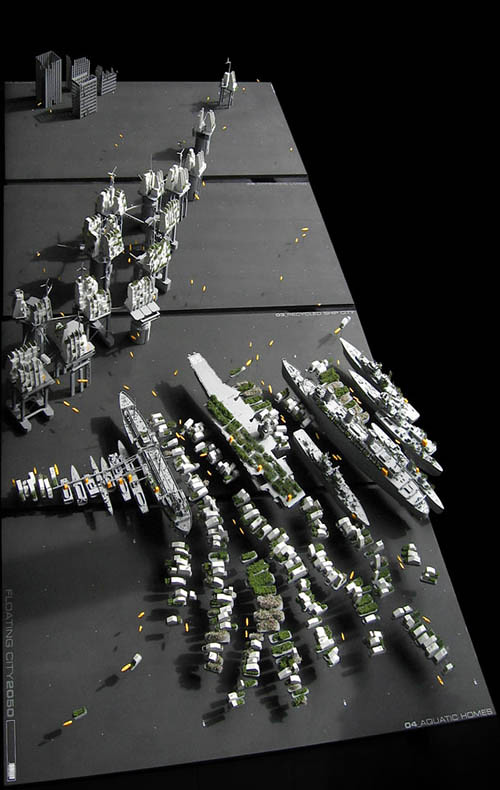

[Images: Models from "

[Images: Models from " [Image: From "

[Image: From " [Image:

[Image:  [Image: Sketch of the

[Image: Sketch of the  [Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:

[Image:  The gardens at Filoli, while they have evolved over the years, have aged so wonderfully primarily because of the thought that went into their planning at the first construction of the house.

The gardens at Filoli, while they have evolved over the years, have aged so wonderfully primarily because of the thought that went into their planning at the first construction of the house. The setting is amazing and was why the house was sited here; to take it all in. The gardens adjacent to the house are Georgian in design to fit in with the design of the house and bring the focus to the Santa Cruz Mountains.

The setting is amazing and was why the house was sited here; to take it all in. The gardens adjacent to the house are Georgian in design to fit in with the design of the house and bring the focus to the Santa Cruz Mountains. The planning of the gardens was actually done as a partnership between the Bourns and the artist,

The planning of the gardens was actually done as a partnership between the Bourns and the artist,  The house was sited so that the rear would have views of the mountains to the East while the entry was put on the west side which lacked a strong view. An olive grove was planted across from the house's entry court to hide a visible water tower in the distance, seen above.

The house was sited so that the rear would have views of the mountains to the East while the entry was put on the west side which lacked a strong view. An olive grove was planted across from the house's entry court to hide a visible water tower in the distance, seen above.

You can see why: wow! I especially love the fog which you can see creeping through the valley.

You can see why: wow! I especially love the fog which you can see creeping through the valley.

The elegant balastrade hides a

The elegant balastrade hides a  This dining room door which connects to an enfilade through the hallways of the house lands on a patio where the family could have breakfast. The wall to the right hides the motor court and is the perfect backdrop for a collection of bonsai.

This dining room door which connects to an enfilade through the hallways of the house lands on a patio where the family could have breakfast. The wall to the right hides the motor court and is the perfect backdrop for a collection of bonsai.

The garage has a clock tower modeled on one by the famous English architect, Christopher Wren. Much of the garden is considered a complete and rare English Renaissance garden.

The garage has a clock tower modeled on one by the famous English architect, Christopher Wren. Much of the garden is considered a complete and rare English Renaissance garden. My favorite spot lies just south of the house. A formal garden is centered upon a reflecting pond and rose garden. A summer house, which I'll share with you later this week, is the perfect place to take tea and enjoy the garden.

My favorite spot lies just south of the house. A formal garden is centered upon a reflecting pond and rose garden. A summer house, which I'll share with you later this week, is the perfect place to take tea and enjoy the garden. The focus of this more elaborate garden still remains the view of the mountains.

The focus of this more elaborate garden still remains the view of the mountains.