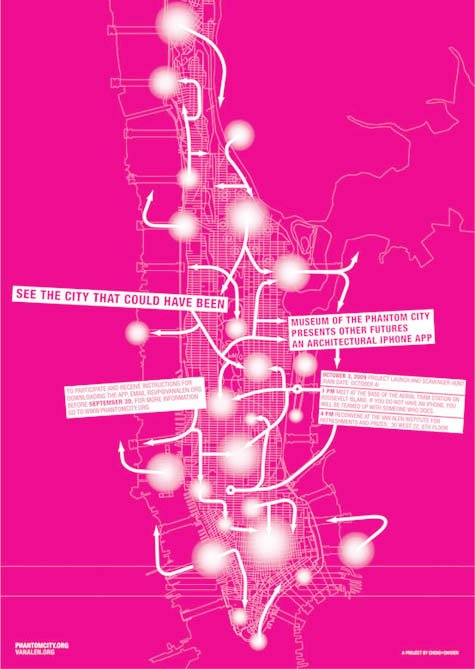

[Image: Museum of the Phantom City by Cheng+Snyder for the Van Alen Institute].

[Image: Museum of the Phantom City by Cheng+Snyder for the Van Alen Institute].A fantastic new iPhone app by Irene Cheng and Brett Snyder has come to market in New York City this autumn. Sponsored by the Van Alen Institute, Museum of the Phantom City is "a public art project that allows individuals to browse visionary designs for the City of New York on their iPhones."

- Users can view images and descriptions of speculative projects ranging from Buckminster Fuller’s dome over midtown Manhattan, to Antonio Gaudi’s unbuilt cathedral, to Archigram’s pop-futurist “Walking City,” all while standing on the projects’ intended sites.

Proposals by Buckminster Fuller are suddenly as real as the Empire State Building – after all, they're both pictured right there on your iPhone...

[Images: Screen shots from Phantom City by Cheng+Snyder].

[Images: Screen shots from Phantom City by Cheng+Snyder].As the New York Times wrote this morning:

- A mile-high dome shades Midtown Manhattan, an airport floats off Battery Park, Harlem is enveloped in a hulking megastructure literally lifting residents out of poverty, and the tallest building in the world, continuously under construction, sprouts from ground zero, growing without end.

“It’s the city that never was but could have been,” said Irene Cheng, an architectural historian. “Sort of an alternate future.”

It would be easy enough, in fact, to put together a tour of building projects that never made it past the recession – New York's so-called "Lost Skyline" – or, for that matter, of the buildings that never made it past the Depression.

You walk past a certain corner on the Upper West Side and your iPhone starts to ring: you're being called by a missing building... Absent structures detected in a wireless blur, leaving messages for you (complete with call-back number).

Electromagnetic voice phenomena in architectural form.

[Image: Screen shot from Phantom City, featuring Superstudio's Continuous Monument].

[Image: Screen shot from Phantom City, featuring Superstudio's Continuous Monument].On one level, of course, it's worth asking whether or not it's a problem that all of these new and exciting visions for 21st-century urban life are only accessible to people rich enough to afford iPhones – but, on another level, why not use the tools that exist, no matter how expensive they might be, in order to try out new models for historical and spatial exploration?

Caving, for instance, requires caving equipment – and not everyone can afford to stock up. But that's no reason to stop exploring the underworld.

At a conference in Turin earlier this summer, I was on a panel with Bruce Sterling and Nicolas Nova, where Nova asked this exact question. Having just shown us all a series of slides in which new ways of interacting with, and learning about, the city had been suggested, he pointed out that most of these things required an iPhone. But do we really want to build and promote the city of tomorrow, if it's effectively inaccessible to a particular class of consumers?

Yet, one could argue, this is exactly what we've done with cars; the spatial needs of the automobile industry have shaped our cities far more than the cultural and economic – and possibly even neurological – needs of those cities' inhabitants.

So will iPhones do to urban information what cars have done to the streetscape?

[Image: The iPhone at work, detecting the Phantom City].

[Image: The iPhone at work, detecting the Phantom City].In any case, back in 2008, in a post that now seems remarkably dated, I suggested that Google Maps should come with a "sci-fi layer" – that is, a layer that would document where in your city certain events had taken place or certain structures had stood in a work of fiction. For instance, the building that Robert Neville's dog runs into in I Am Legend or the trainyard from Escape From New York, the apartments from Make Room! Make Room!, the high-rise penthouse from The Day After Tomorrow...

Those are Manhattan-centric examples, of course, and drawn only from science fiction, but this could easily be expanded to include landscapes and structures elsewhere, from the deserts of the Empty Quarter to central Paris, and it could include other genres, from the poems of John Ashbery to Howl to The Great Gatsby.

You could even have a "mythology layer" – roaming around Scandinavia, tracking Thor or digging for the roots of Yggdrasil – or a "theology layer": you go to Israel and your iPhone short-circuits from the laminations of charged geography around it. Pillars of salt, sacred basements, dead walls and abandoned forts.

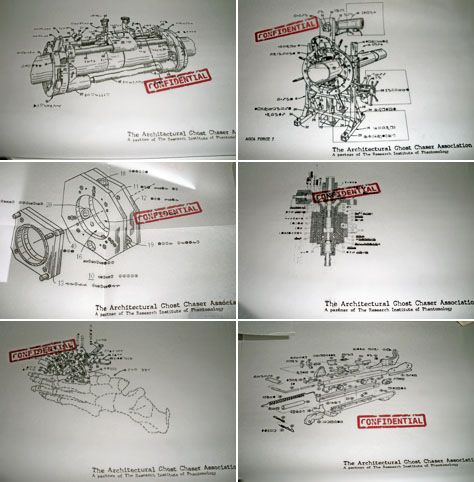

In fact, I'm further reminded of a project produced this past summer by Sally Hsu, one of my students at Urban Islands down in Sydney. Hsu came up with something she called the Research Institute of Phantomology, a fake historical research society whose specially-invented machines could detect missing buildings: structures that had been demolished and lost to history. You could use these throughout the Sydney Harbor – or specifically on Cockatoo Island, where our studio was set – in order to trace the architectural remains of history.

One of those devices, according to Hsu, was the Architectural Ghost Chaser: it would lead historians directly to the ruins of old buildings in the earth.

[Image: Patent diagrams for an "Architectural Ghost Chaser" by Sally Hsu; Urban Islands 2009].

[Image: Patent diagrams for an "Architectural Ghost Chaser" by Sally Hsu; Urban Islands 2009].A tongue-in-cheek proposal, of course – Hsu even made patent diagrams to illustrate it, as well as a fake cover for New Scientist featuring the remarkable device – it nonetheless kicked-off an interesting conversation about demolished buildings, urban archaeology, and the strategies through which we could detect the ruins of the past if physical excavation is not an option. After all, we've already got things like ground-penetrating radar – through which we can map and explore an ancient Roman city beneath Wroxeter, England, without digging a single hole – and we've even got muon detectors. But imagine discovering new archaeological sites through an iPhone app!

So why not build a tricked-out PKE Meter attuned to architectural space? At the exact intersection of Sally Hsu's Institute of Phantomology and the iPhone?

In other words, why not create something like the Museum of the Phantom City?

Cheng+Snyder's free download opens up a new kind of historical spectating: architectural tourism of the unbuilt. Perhaps someday we'll be done with monographs, traveling exhibitions, and even senior thesis reviews; we'll simply upload all our projects into the Phantom City and let the world decide their worth. Crowds of tourists mill about on 13th Street, looking around at the imaginary buttresses of a superstructure you've spent three years digitally assembling.

Download the app via the iTunes store and see for yourself.

No comments:

Post a Comment