[Image: From Blend; those aren't typos, by the way – it's Dutch].

[Image: From Blend; those aren't typos, by the way – it's Dutch].Little Venice is a small riverine village east of Notting Hill on the manmade canals of Victorian London. Its waterways were all designed in the early 1800s by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the same engineer behind the machinery that excavated London's first Tube tunnels.

Now, however, the Romantic canals and artificial rivers of Little Venice offer something of an unintended glimpse, or working model, of the London yet to come.

"Tide levels are steadily increasing owing to a combination of factors," the UK's Environment Agency warns. "These [factors] include higher mean sea levels, greater storminess, increasing tide amplitude, the tilting of the British Isles (with the south eastern corner tipping downwards) and the settlement of London on its bed of clay."

Post-glacial rebound is the technical term for this "tilting of the British Isles." That tilt comes as northern Scotland's deglaciated mountain valleys rise steadily upward, decompressing from the weight of lost ice caps. Like a geologically-themed, slow-motion amusement park ride, the British Isles are thus "tilting," with Scotland's rebound pushing London into the sea.

Climate change only adds to the city's worries.

[Image: London, flooding; via the Environment Agency – if you're a Londoner, type in your postcode and see if you're at risk from water...].

[Image: London, flooding; via the Environment Agency – if you're a Londoner, type in your postcode and see if you're at risk from water...].Short of capping the Highlands in new glaciers of lead, however, or attaching gigantic hot air balloons to the spires of churches to pull the city skyward, London will eventually flood: its undersea fate is geologically inevitable. Whether this occurs in a hundred years or a hundred centuries, London will become a city of canals – before it is lost to the sea entirely. It is a new Atlantis, sinking deeper each day into the oceanic embrace of hydrology.

Yet is worrying about this fate the appropriate response? Perhaps such an outcome isn't tragic at all. Perhaps, if we view this future with a certain architectural curiosity, we can respond with something like enthusiasm.

In which case: what future city will we see upon the Thames?

In the estuarial distance, perhaps a thousand new artificially intelligent Thames Barriers will lift and fold their bulwarked walls against the onslaught of the sea. Moving levees, crawling and motorized – a kind of hydrological Maginot Line – insect-like and powered by tides, will encircle the British archipelago. We'll drive across inland lagoons on floating motorways.

House-boats and cargo ships will anchor ten meters above the pavements of Trafalgar, unloading passengers and cargo, Admiral Nelson now wreathed in seaweed. Adventure tourism firms will lead scuba diving expeditions through the reefs of Westminster, wealthy clients spear-fishing eels in the back rooms of flooded estate agents.

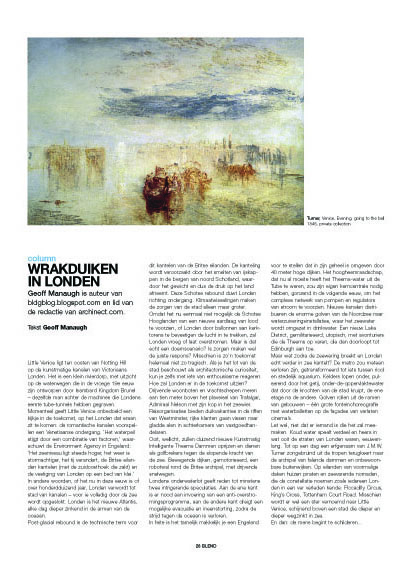

[Image: J.M.W. Turner].

[Image: J.M.W. Turner].London's underwater fate thus presents us with at least two intriguing lines of speculation. On the one hand you've got possible next steps for Greater London's imperial flood control regime; on the other, a vision of evacuation, collapse and abandonment after the city's oceanic war has been lost. Either way, the future of London is with the sea.

It's easy to imagine, in fact, that the entire English coastline might soon be buttressed behind 40-meter high locks and channels. Thames Water, already struggling to keep the Tube dry from river overflow, would need its own nuclear power plants, droning into the 27th century, just to fuel its complex networks of pumps and aquatic regulators. New canals, distributing North Sea storm surges up toward marshland desalination plants, could store that water in huge inland seas, well-protected reservoirs processed for drinking. A new Lake District, militarized, utopian, walled with concrete, might be visited by future Wordsworths, Coleridge and his ancient mariner setting sail up the Thames, now freshly dredged as far as Edinburgh.

But once those defenses fail, and London tilts further beneath the waves?

[Image: J.M.W. Turner].

[Image: J.M.W. Turner].The London Underground will be lost immediately, transformed into something between sewer and urban aquarium. Cellars and the steps that lead to them will make London a city of valves, pulsing from below with subsurface waters that burst up and outward from the windows of buildings, all of London a simulacrum of Versailles – an unintended architecture of choreographed fountains – showing off in arcs sprayed upon the facades of abandoned shopping malls.

Perhaps no one will be around to witness all this: cold water will lap across the bleached dome of St. Paul's unseen, for centuries...

Till, someday, a distant heir of J.M.W. Turner will return sunburnt from the tropics to find London an archipelago of failed sea walls and water-logged high-rises, the suburbs an intricate filigree of uninhabited canals, bonded warehousing forming atolls amidst sandbanks and deltas. Amidst new islands of former rooftops, he will rename the constellations to fit British geography as it used to be: Piccadilly Circus, King’s Cross, Tottenham Court Road, all burning above a city that quietly rushes with black waves.

Perhaps there will even be a star named after Little Venice, as its namesake rebounds further and further beneath the sea.

(Note: A slightly different version of this article, translated into Dutch, was published several months ago in Blend magazine – for whom I continue to write monthly columns, in case you're in Holland and you need something to read... And if you're as dizzyingly in love with J.M.W. Turner as I am, consider reading Peter Ackroyd's brief biography of him this winter).

No comments:

Post a Comment