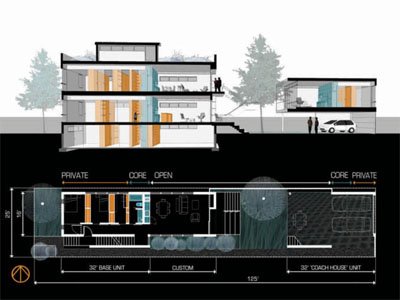

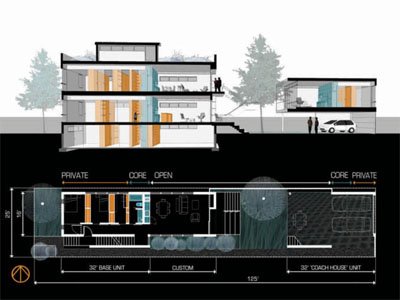

Scion Floorplan

"A competition, open to the design community, where you are asked to design Scion's new dealership showroom. The competition is an opportunity for designers to work with real world design constraints, get noticed by judges working in the design industry, be creative, and possibly win $5,000."

The World Mammoth Museum

A two-stage competition for the International Mammoth and Permafrost Museum in Yakusak, Russia as "part of an ambitious program of creation of a park dedicated to individual and family excursions according to the environmental, ethnography and history themes [and which] lays a great emphasis on the findings of woolly mammoths, frozen more than 10,000 years ago."

Architectural engineering design.autocad career .learnin,news,architecture design tutorial,

Friday, September 29, 2006

Two Competitions

A couple new competitions that landed in my inbox:

Project New Orleans

Here's a site I learned of in studio yesterday. It's called Project New Orleans. It aims to be a complete archive of all the (student?) projects being done for the reconstruction of New Orleans, from Single Family Housing and Urban Design to Flood and Transportation Infrastructure. Big and small, they have it all...or do they? It appears that many gaps exist on the page as of today (expect some "Not Found" errors on certain links), though this points to the need for people involved to fill in those gaps. So if you've worked on a job for reconstruction in New Orleans, be it listed on the PNO web page or not, contact the site administrators to help them with their ongoing research...whenever they get the contact information up there.

If you just want to browse the projects that are posted, here's some of interest:

If you just want to browse the projects that are posted, here's some of interest:

::ecoMOD2:preHAB by students at the University of Virginia

:: URBANbuild by students at Tulane University

:: High Density Housing by students at CCNY

:: reGrow by students at MIT

:: Inter-Living Systems and Sea Level by students at University of Kansas

:: Inhabiting the Fluid Terrain projects by University of Pennsylvania students

Thursday, September 28, 2006

Today's archidose #34

Neurosciences Wedges by ken mccown

The Neurosciences Institute in San Diego, California by Tod Williams and Bille Tsien.

To contribute your Flickr images for consideration, just:

:: Join and add photos to the archidose pool, and/or

:: Tag your photos archidose

Wednesday, September 27, 2006

City of the Pharaoh

[Image: Cecil B. DeMille's not yet lost city – the set of The Ten Commandments, during filming].

[Image: Cecil B. DeMille's not yet lost city – the set of The Ten Commandments, during filming]."In 1923," we read, "pioneer filmmaker Cecil. B. DeMille built the largest set in movie history for his silent (and early Technicolor) epic, The Ten Commandments. It was called 'The City of the Pharaoh.'"

Constructing DeMille's instant city was no half-effort: "Sixteen hundred laborers built hieroglyph-covered walls 110 feet tall, flanked by four statues of Ramses II and 21 sphinxes, 5 tons each. DeMille populated his city with 2,500 actors and extras, housing them in tents on an adjacent dune."

[Image: A scene from The Ten Commandments, via NPR].

[Image: A scene from The Ten Commandments, via NPR].Not one to leave his creation around for others to use in their own cinematic ways, "DeMille ordered that the entire edifice be dismantled... and secretly buried. And there it lay, forgotten, for the next 60 years," eventually becoming known as the "lost city of Cecil B. DeMille."

But then, in 1983, "a group of determined film buffs – inspired by a cryptic clue in DeMille's posthumously published Autobiography – located the remains of the set. (...) They brought in ground-penetrating radar to scan the sands, and hit pay dirt: the dune-entombed remains of DeMille's dream."

[Image: The lost city, via NPR].

[Image: The lost city, via NPR].Peter Brosnan and John Parker – the "film buffs" mentioned above – arrived at the site to find themselves "in a field of plaster statuary... [T]here had been big storms, and more set was uncovered than had been seen in 30 years." They thus proceeded with the excavation... about which more can be read here.

Meanwhile, something about this story reminds me (very vaguely) of Skara Brae, a 4000-year old Stone Age village uncovered not by archaeologists but by an especially violent seasonal storm on the far west coast of Scotland.

"In the winter of 1850," Orkneyjar tells us, "a great storm battered Orkney. Nothing particularly unusual about that, but on this occasion, the combination of Orkney's notorious winds and extremely high tides stripped the grass from a large mound known as Skerrabra. The storm revealed the outline of a series of stone buildings that intrigued the local laird, William Watt of Skaill. So he embarked on an excavation of the site."

[Image: Skara Brae, via Orkneyjar].

[Image: Skara Brae, via Orkneyjar].Orkneyjar goes on to explain that, "[b]ecause of the protection offered by the sand that covered the settlement for 4,000 years, the buildings and their contents are incredibly well-preserved. Not only are the walls of the structure still standing and alleyways roofed with their original stone slabs, but the interior fittings of each dwelling give an unparalleled glimpse of life as it was in Neolithic Orkney."

In any case, combine Skara Brae and DeMille's lost city – then add a few ten thousand years – and you get future archaeologists uncovering, by accident, with the help and assistance of an unseasonal storm, the outlines of a buried city. Washington D.C., say, or perhaps Springdale, Utah. Thing is, these future archaeologists conclude that the city wasn't an actual dwelling place, not a real place to live – they discover far too many parking lots, for instance, and can't believe anyone would willingly live surrounded by those things – instead, they think, the city had been a monumental film set.

Excavations continue – leading to the controversial conclusion that human civilization in North America was really a massive piece of performance art, from sea to shining sea – a cinematic installation upon the plains – and so whatever film had been made there must surely still exist...

Thus begins a whole new, Paul Austerian chapter of future archaeology – in which they hunt for the lost and secret films of a buried North America.

(Thanks, Juke!)

Tuesday, September 26, 2006

Today's archidose #33

IMG_1080.JPG by Evan Burr

Walt Disney Concert Hall by Frank Gehry.

To contribute your Flickr images for consideration, just:

:: Join and add photos to the archidose pool, and/or

:: Tag your photos archidose

Fitzcarraldo

As a way to kick-off the year long South American project in our Urban Design studio, our class watched Werner Herzog's 1981 feature Fitzcarraldo. (Warning: some spoilers follow.)

The film tells the story of Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald (called Fitzcarraldo by the locals), an eccentric foreigner in the jungles of early 20th-century Peru determined to bring opera to the frontier town (as he calls it) where he lives. To raise money for the construction of an opera house he sets out to extract rubber from trees in an inaccessible part of the jungle. Rather than battling rapids upstream, his plans involves "coming from the rear" by carrying a steamship over land from one river to another where they almost meet. But the land between the two rivers is extremely steep and requires strength, ingenuity, and time to traverse. Fitzcarraldo is aided by a tribe of indigenous peoples that have other motives for the seemingly impossible feat.

Still found at Images

Although I hadn't heard of the film before last nite's screening, apparently it is very well known, not so much for its story but for its production history, extreme shooting conditions, and off-screen friction. (A documentary on the making of the movie was even made, called Burden of Dreams.) Apparently, Herzog was almost halfway through filming when Jason Robards -- his first choice for Fitzcarraldo -- became ill and had to leave the film. It was about a year from the start of shooting when they resumed with Klaus Kinski, a familiar Herzog face who clashed numerous times with the director and the locals during filming. While watching the film, this tension isn't apparent (maybe some frustration, the frustration of filming in the Amazon, is), but the realism of moving the ship over land and the subsequent journey down the rapids clearly indicates minimal special effects. It looks like they are actually moving the steamship up and over the hill via winches and sheer force. And from all accounts I've read, that is the case.

Still found at Images

To me the importance and popularity of the film's making, as much as (or over) the film itself, points to a parallel between the character of Fitzcarraldo and the director himself. Herzog could have quit production in the Amazon entirely after Robards left, but he persevered, much like Fitz never gives up in failed attempt after failed attempt at raising money for his beloved opera house. By the end of the film it seems that fate has told Fitz that his dream will never come true, but even then he finds a way to make the most of an adverse and defeating situation.

The film tells the story of Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald (called Fitzcarraldo by the locals), an eccentric foreigner in the jungles of early 20th-century Peru determined to bring opera to the frontier town (as he calls it) where he lives. To raise money for the construction of an opera house he sets out to extract rubber from trees in an inaccessible part of the jungle. Rather than battling rapids upstream, his plans involves "coming from the rear" by carrying a steamship over land from one river to another where they almost meet. But the land between the two rivers is extremely steep and requires strength, ingenuity, and time to traverse. Fitzcarraldo is aided by a tribe of indigenous peoples that have other motives for the seemingly impossible feat.

Still found at Images

Although I hadn't heard of the film before last nite's screening, apparently it is very well known, not so much for its story but for its production history, extreme shooting conditions, and off-screen friction. (A documentary on the making of the movie was even made, called Burden of Dreams.) Apparently, Herzog was almost halfway through filming when Jason Robards -- his first choice for Fitzcarraldo -- became ill and had to leave the film. It was about a year from the start of shooting when they resumed with Klaus Kinski, a familiar Herzog face who clashed numerous times with the director and the locals during filming. While watching the film, this tension isn't apparent (maybe some frustration, the frustration of filming in the Amazon, is), but the realism of moving the ship over land and the subsequent journey down the rapids clearly indicates minimal special effects. It looks like they are actually moving the steamship up and over the hill via winches and sheer force. And from all accounts I've read, that is the case.

Still found at Images

To me the importance and popularity of the film's making, as much as (or over) the film itself, points to a parallel between the character of Fitzcarraldo and the director himself. Herzog could have quit production in the Amazon entirely after Robards left, but he persevered, much like Fitz never gives up in failed attempt after failed attempt at raising money for his beloved opera house. By the end of the film it seems that fate has told Fitz that his dream will never come true, but even then he finds a way to make the most of an adverse and defeating situation.

Monday, September 25, 2006

Monday, Monday

My weekly page update:

BMW Plant Leipzig in Leipzig, Germany by Zaha Hadid Architects.

The updated book feature is Zaha Hadid: BMW Central Building, edited by Todd Gannon.

Some non-Zaha Hadid links for your enjoyment:

BMW Plant Leipzig in Leipzig, Germany by Zaha Hadid Architects.

The updated book feature is Zaha Hadid: BMW Central Building, edited by Todd Gannon.

Some non-Zaha Hadid links for your enjoyment:

Arkinetia

Well-done architecture blog, in Spanish. (added to sidebar under blogs::architecture; thanks Damian!)

Francis Morrone Q&A

An interview with one of the Blowhards. (thanks Andrew K!)

Sunday, September 24, 2006

House of Light

Before the recent move I "clipped" this article at PingMag to read later...well, I'm finally getting around to it today. "Staying in James Turrell's House of Light" describes "a modern-built, traditional-style Japanese house where people can stay to experience light in a variety of specific conditions that [Turrell] has arranged for, all centered around a sky-viewing room."

For those unfamiliar with James Turrell, his signature installations are skyspaces that feature a ceiling aperture open to the sky, making it appear flattened, almost pure color. These spaces are intended to influence the viewer's way of thinking via perception. As can be seen by this set, I'm smitten with them.

And after seeing the PingMag article, it looks like I have another reason to return to Japan, to not just sit in a Turrell but to stay in one.

For those unfamiliar with James Turrell, his signature installations are skyspaces that feature a ceiling aperture open to the sky, making it appear flattened, almost pure color. These spaces are intended to influence the viewer's way of thinking via perception. As can be seen by this set, I'm smitten with them.

And after seeing the PingMag article, it looks like I have another reason to return to Japan, to not just sit in a Turrell but to stay in one.

Saturday, September 23, 2006

Today's archidose #32

Inside a rainbow by rutger_spoelstra

Offices La Defence in Almere, Netherlands by UN Studio (Ben van Berkel, Caroline Bos).

To contribute your Flickr images for consideration, just:

:: Join and add photos to the archidose pool, and/or

:: Tag your photos archidose

Friday, September 22, 2006

Edinburgh

In a (very) short story called "The Antipodes and the Century," author Ignacio Padilla describes "a great Scottish engineer, left to die in the middle of the desert, [who] is rescued by a tribe of nomads." Upon recovery, the engineer soon "inspires" his saviors "to build an exact replica of the city of Edinburgh in the dunes."

[Image: Edinburgh, as photographed by Jim Webb in 2002].

[Image: Edinburgh, as photographed by Jim Webb in 2002].

There, "amidst the rocks of the Gobi," Padilla writes, Kirghiz nomads are taught "the exact height that Edinburgh Castle must attain, the precise length of the bridge that connects the High Street with Waverly Station, the correct calculations necessary to establish the perimeter of Canongate Cemetery, [and] the true distance between the two spires of St. Giles' Cathedral."

With that knowledge – and with lots of rocks – they construct "an elephantine fortress of streets, bridges, and windows." It is "a shimmering haze of towers" that blends in architecturally with the inferior mirages of the desert horizon.

Until it is buried by a sandstorm, then, this new, replicant Edinburgh functions as "a kind of global map in the very heart of the Gobi Desert," we read, "a vague though tangible diorama of the cosmos, its center a replica of the Scottish capital."

(See also Huangyangtan: or, Tactical geoannexation, Part II, at Pruned).

There, "amidst the rocks of the Gobi," Padilla writes, Kirghiz nomads are taught "the exact height that Edinburgh Castle must attain, the precise length of the bridge that connects the High Street with Waverly Station, the correct calculations necessary to establish the perimeter of Canongate Cemetery, [and] the true distance between the two spires of St. Giles' Cathedral."

With that knowledge – and with lots of rocks – they construct "an elephantine fortress of streets, bridges, and windows." It is "a shimmering haze of towers" that blends in architecturally with the inferior mirages of the desert horizon.

Until it is buried by a sandstorm, then, this new, replicant Edinburgh functions as "a kind of global map in the very heart of the Gobi Desert," we read, "a vague though tangible diorama of the cosmos, its center a replica of the Scottish capital."

(See also Huangyangtan: or, Tactical geoannexation, Part II, at Pruned).

Thursday, September 21, 2006

Three Bits

One::

Corflot notifies me that their 2006 Design Salary Survey is up and running. Unlike previous years, this survey features an architecture concentration in addition to the other design-oriented areas of concentration. Take it now.Two::

Good Magazine features the article "Chasing Zero" by Ben Jervey, author of The Big Green Apple. In it the author documents his "month-long experiment in extreme urban environmentalism."Three::

My DSL modem arrived in the mail last night! After some initial problems connecting, it's now up and running. What does this mean? Mainly that when I get home tonite I'll send out my backlog of subscription notices to my weekly readers. And after that those notices will return to their regular frequency, once a week.

Alluvial Bends

Wednesday, September 20, 2006

Learning from Lawndale

The Chicago Architectural Club today announces the winner of the 2006 Burnham Prize, Learning from North Lawndale: Defining the Urban Neighborhood in the 21st Century. The Burnham Prize, a three-month fellowship at the American Academy in Rome, will be awarded to Kim Nigro of Chicago Illinois. Ms. Nigro recently received her Masters degree in Architecture from the University of Illinois-Chicago (with a B.Arch from Kansas State University, like me), and is working as a project manager at the Chicago-based architecture firm, Wilkinson-Blender Architects.

Her project rethinks the traditional Greystone of North Lawndale with affordability, sustainability, and prefabricated construction as the overriding concepts.

An opening reception is tonight, Wednesday September 20, 2006, 5:30 PM at the Chicago Architecture Foundation's Atrium Gallery, 224 S. Michigan in Chicago.

Her project rethinks the traditional Greystone of North Lawndale with affordability, sustainability, and prefabricated construction as the overriding concepts.

An opening reception is tonight, Wednesday September 20, 2006, 5:30 PM at the Chicago Architecture Foundation's Atrium Gallery, 224 S. Michigan in Chicago.

Book of the Moment

Did Someone Say Participate? An Atlas of Spatial Practice is a book responding to "globalization at work." Editors Markus Miessen and Shumon Basar contend that a "new atlas is being re-drawn for the 21st century" and that their book "re-draws the map of participatory, spatial practice that is a function of such shifts."

The thick and heavily illustrated book has the requisite eye candy (check out the book's web page for some sneaks) set within a highly theoretical and potentially controversial topic, namely the architect's role in globalization.

The thick and heavily illustrated book has the requisite eye candy (check out the book's web page for some sneaks) set within a highly theoretical and potentially controversial topic, namely the architect's role in globalization.

Tuesday, September 19, 2006

Upper West Side

This last Sunday was my first "day off" since Labor Day and the start of Urban Design studio. Rather than relaxing at home, my wife and I took the train into Manhattan and walked around the Upper West Side and Central Park, two beautiful areas of the city. Here's some pictures that I've posted on Flickr.

The Lotus Garden, a hidden gem of a garden on the roof of a parking garage. It takes a key to gain entry, except on Sunday afternoon. I'm happy to say I have one now and can go there and relax whenever I feel like it. A few more pics of the garden here.

Pomander Walk, a group of small, London-esque buildings done in 1921. They are now dwarfed by their neighbors, making their small size seem even smaller.

Symphony Space by Polshek Partnership. Entry detail.

The recently-completed Gaynor School by Rogers Marvel Architects.

View of Midtown East skyscrapers from Central Park.

The Lotus Garden, a hidden gem of a garden on the roof of a parking garage. It takes a key to gain entry, except on Sunday afternoon. I'm happy to say I have one now and can go there and relax whenever I feel like it. A few more pics of the garden here.

Pomander Walk, a group of small, London-esque buildings done in 1921. They are now dwarfed by their neighbors, making their small size seem even smaller.

Symphony Space by Polshek Partnership. Entry detail.

The recently-completed Gaynor School by Rogers Marvel Architects.

View of Midtown East skyscrapers from Central Park.

Today's archidose #31

Rotating its way to the sky by bjorn_cph

Santiago Calatrava's Turning Torso tower in Malmo, Sweden.

To contribute your Flickr images for consideration, just:

:: Join and add photos to the archidose pool, and/or

:: Tag your photos archidose

HdM Does High-rise

Cisar reports about the unveiling of a tower for Roche, a health-care company, by Herzog & de Meuron. If built, the tower would be located in Basel and would be Switzerland's tallest building. Estimated completion is 2011.

This design follows from the recent trend of torquing, twisting, and spiraling towers, particularly those of Santiago Calatrava. Here, the result is not so much mathematical in nature but in response to zoning requirements, program, organization, and a series of voids that traverse the tower, per this diagram. In some ways, this trend is born from the attempt to distinguish certain designs from others, but the more they are created the more they tend to resemble each other.

More photos are available in scisar's flickr set on HdM.

(via Archinect)

This design follows from the recent trend of torquing, twisting, and spiraling towers, particularly those of Santiago Calatrava. Here, the result is not so much mathematical in nature but in response to zoning requirements, program, organization, and a series of voids that traverse the tower, per this diagram. In some ways, this trend is born from the attempt to distinguish certain designs from others, but the more they are created the more they tend to resemble each other.

More photos are available in scisar's flickr set on HdM.

(via Archinect)

Monday, September 18, 2006

Monday, Monday

My weekly page update:

Beverly Skyline Residence by Bercy Chen Studio.

Some unrelated links for your enjoyment:

Beverly Skyline Residence by Bercy Chen Studio.

Some unrelated links for your enjoyment:

LEED Boot Camp

"Helping people get more acquainted with the LEED exam." (added to sidebar under professional)

DVD Ideas

Looking for films on architecture?. Check out this site's architecture category for some ideas. (added to sidebar under guides)

Saturday, September 16, 2006

Michielangelo becomes Eikongraphia

FYI, readers:

After 8 months and 88 posts the Michielangelo blog moves to a new site: www.eikongraphia.com. The name "Eikongraphia" is derived from the original Greek word for Iconography.This change has been made in my sidebar. Thanks for the update, Michiel.

The new Eikongraphia blog has some important new features:

:: The iconography database is easily accessible by a new interface that presents all filed projects by Theme and within a Top 10 chart.

:: The Narrative gives an insight in the theoretical background of iconography.

:: The Article that Michiel wrote in advance of the Projective Landscape Conference.

Friday, September 15, 2006

Today's archidose #30

DSC02595 by sterne_nkr707

WoZoCo's Apartments in Amsterdam by MVRDV.

To contribute your Flickr images for consideration, just:

:: Join and add photos to the archidose pool, and/or

:: Tag your photos archidose

Thursday, September 14, 2006

Sex and the City

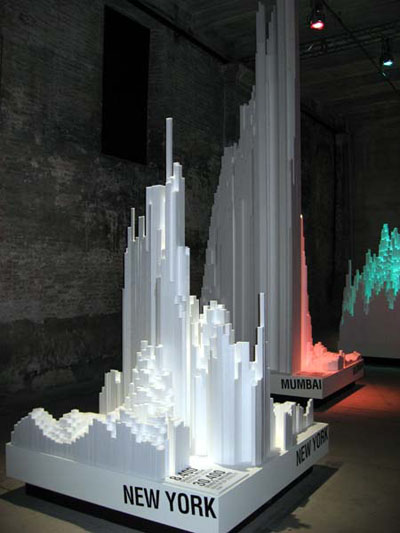

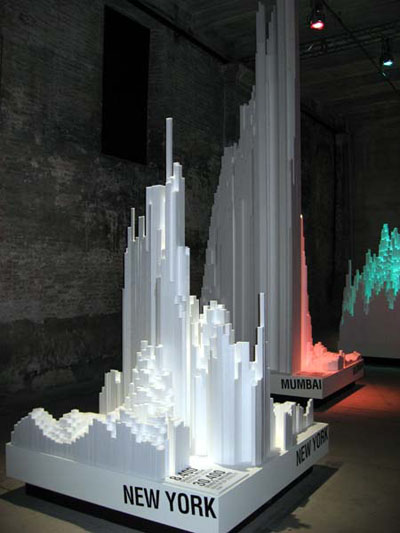

New York-based architect Margaret Helfland writes a two-part coverage of the 10th Venice Architecture Biennale over at ArchNewsNow.

One of my professors, Grahame Shane, called the show superficial but with some interesting exhibitions, though Helfland seems to be taken with the show, calling it "a call-to-arms for advocacy and engagement in the political process." Part one here and part two here.

One of my professors, Grahame Shane, called the show superficial but with some interesting exhibitions, though Helfland seems to be taken with the show, calling it "a call-to-arms for advocacy and engagement in the political process." Part one here and part two here.

Tuesday, September 12, 2006

Quick list 4

Tomorrow morning BLDGBLOG rolls itself out upon the American interstate highway system to make its slow way over to the apocalypse of Los Angeles – via Chicago, Denver, Boulder, and Springdale, Utah, where a few pints of Polygamy Porter and some long hikes in Zion National Park strongly beckon – all the while hoping to maintain some sort of regular posting schedule, as I have about 2.173 billion things I want to tell everyone about.

Tomorrow morning BLDGBLOG rolls itself out upon the American interstate highway system to make its slow way over to the apocalypse of Los Angeles – via Chicago, Denver, Boulder, and Springdale, Utah, where a few pints of Polygamy Porter and some long hikes in Zion National Park strongly beckon – all the while hoping to maintain some sort of regular posting schedule, as I have about 2.173 billion things I want to tell everyone about. First off, British architect Norman Foster "has been enlisted by the King of Jordan for his most grandiose project yet – a canal carved through the desert to rescue the Dead Sea from environmental disaster." Foster's plan "is to carry sea water from the Gulf of Aqaba to replenish the Dead Sea, which has shrunk by a third over the past 50 years and faces total evaporation." The water will travel through a "sequence of canals and pipelines," moving "down through the arid Arava valley in southern Israel and Jordan to the salt lake at the lowest point on earth, 415 meters below sea level.”

We wish him luck – then we refer you to the great man-made river of Libya.

Elsewhere, metallic, alcohol-detecting flowers have been "grown in a laboratory in China." These "spectacular flower-like nanostructures" are each "made up of bundles of nanorods 15nm wide. They were made by blasting a zinc-containing solution with ultrasound."

Elsewhere, metallic, alcohol-detecting flowers have been "grown in a laboratory in China." These "spectacular flower-like nanostructures" are each "made up of bundles of nanorods 15nm wide. They were made by blasting a zinc-containing solution with ultrasound." This bouquet even conducts electricity: "To make a sensor the researchers wired up two patches of the flowers into a circuit."

Next up: the flowers escape and cross-breed with uranium, forming an unkillable flowering alloy that soon decimates New York City. Within ten years, the cities of North America resemble a metallized return to the Jurassic era, complete with bio-iron vines and moving fogs made entirely from electricity...

As you ponder that fate, check out Architecture Radio's podcast of a talk by Steven Ehrlich, an architect based in Culver City, Los Angeles; then give a listen to AR's earlier lecture by border-crossing architect Teddy Cruz. Then, while your ears recover, this video-tour of a data storage warehouse is worth a minute or two of your time.

Equinix Internet Business Exchange centers, we see, "serve as core hubs for critical IP networks and Internet operations worldwide." They are huge, air-conditioned warehouses full of humming CPUs and bundled cables, watched over by CCTV.

- With direct access to more than 200 networks, including all of the top global Tier 1 networks, Equinix's network-neutral IBX centers and services overcome the limitations of existing data center, network and Internet operations through direct interconnection to the largest aggregation of networks for unmatched service diversity, flexibility and reliability. At Equinix, customers can directly access the providers that serve over 90% of the world’s Internet networks and users.

In other words, using hinged networks of cables and steel restraining belts, the growing branches of trees can be forced to assume the shape of a masted ship.

Is it the self-pruning future of architecture...?

More soon... And I'll try to keep posting from the road.

(Earlier: Quick list 3, et cetera).

Today's archidose #29

DSCF1895.JPG by schopaia

Rock Valley College Starlight Theatre in Rockford, Illinois by Studio Gang/O'Donnell (now Studio Gang). Check out schopaia's extensive Flickr set on the Theatre.

To contribute your Flickr images for consideration, just:

:: Join and add photos to the archidose pool, and/or

:: Tag your photos archidose

4 Classes

Having my fourth of four classes start yesterday, I thought I would briefly describe each of them for those interested. For those who haven't been "following" this page, I'm talking about the Urban Design Program (PDF link) at City College (part of CUNY). The department is headed by Michael Sorkin and is two semesters in length.

Urban Design Studio

History of Urban Space

Reading the City

Urban Ecologies

Urban Design Studio

Unlike previous years (since the institution of the studio component in 2000) where each semester focused on a separate project -- one ideal and hypothetical, the other in NYC -- our studio has one project for the whole year. It is the design of a self-sufficient town in South America. Also, unlike previous years, this project is more practical, in that we'll work with the town (in conjunction with a local university) with the intention of implementation of the plan in some form, probably over time long after the studio's completion. It's highly ambitious and exciting for what's a relatively short period of time to tackle the design of a city. It goes without saying that issues of sustainability, among many others, are crucial to approaching the city design, making the project much more timely and important. The studio is taught by Sorkin.

History of Urban Space

Taught by Grahame Shane, this class is built around his new book Recombinant Urbanism: Conceptual Modeling in Architecture, Urban Design and City Theory as well as key texts like Lynch's Good City Form and Rowe's Collage City. This was the last class to start (yesterday) and we were treated to a guest lecture on Aranya (or Sector 72, as it's known locally) a mixed-income development in Indore, India by perhaps that country's most famous architect, Balkrishna Doshi. The town is a fascinating example of urban design based on an evolutionary view where occupants are given freedom with not only building design but use. Doshi's plan created plots and laid out services, and while he contributed many house designs for the area, they are the minority. In many ways, it's the opposite of what many might think of with larger developments, in terms of control, level of completion and user input. Immediately, I get the sense that the class will focus on unconventional historical models and methods for looking at the city and urban design.

Reading the City

Film has always been a popular subject for architects, and this class uses film noir as a device for analyzing the city. Unlike other genres (if film noir can be called one is a point of contention but one I will not go into here), one associates noir with the city more than any other place. The dark corners, wet streets, hotels, offices, and other spaces and places of the city litter films of this type. Situate within their dark and paranoid narratives, these films parallel America's thinking towards the city around the end of the war and the move from cities to suburbs. The class fits alongside the others, even though it's relationship to urban design or architecture is not as direct; it's indicative of the program's embrace of other disciplines as well as the intertwined and interdependent nature of expression and thinking. Taught by Joan Copjec.

Urban Ecologies

This class comes full circle back to the design studio and its sustainable focus. Here, ways of thinking about the environment, both historically and in the present, are valued above practical application of ecological principles. This follows from the notion that in order to know what to do about the environment we must rethink the way we look at the environment, primarily as a something we are a part of, not separate from. This is probably the most thought-provoking class (taught by landscape professor Achva Stein), especially in terms of finding ecological change at a time when economy drives decision making. Can ecological thinking work with economical thinking? Or will that decision be made for us, like it or not? We'll see.

Design in the World

Over on Archinect, I've posted a lengthy interview with Detlef Mertins, Chair of the Architecture Department at the University of Pennsylvania.

[Image: Detlef Mertins; photograph by Kristine Allouchery].

[Image: Detlef Mertins; photograph by Kristine Allouchery].

There we discuss the changing nature of architectural education: what teaching strategies, points of reference, and technologies (such as robotic assembly and 3D printing) can be used most effectively in the classroom. We go through everything from Mies van der Rohe vs. Toll Brothers to the use of algorithms in architectural design; from LEED certification and green building practice to comic books, Archigram, and the use of narrative fiction in student presentations.

On algorithms, for instance, Mertins remarks that the ongoing controversy over whether or not to use mathematics as a generator of architectural form overlooks the fact that reliance on algorithms is simply part of a long "tradition of architects seeking to learn from nature’s capacity to produce forms, patterns and structures of extraordinary beauty and functional prowess. Algorithmic design taps into a giant reservoir of mathematical models already at work in the processes that constitute the universe. In that respect, it’s still a form of mimesis."

[Images: Student work from the University of Pennsylvania – in this case, a project by Justin Coleman, Amy Johnson, Jaime Lee, and Herman Mao, from their 3rd Year course with professor Cecil Balmond. See Archinect for more].

[Images: Student work from the University of Pennsylvania – in this case, a project by Justin Coleman, Amy Johnson, Jaime Lee, and Herman Mao, from their 3rd Year course with professor Cecil Balmond. See Archinect for more].

It's a good interview, if I do say so myself. For me, as well, it comes with the well-timed realization that if someone as intelligent, articulate, patiently deliberative, and simply good humored as Detlef Mertins can survive the city of Philadelphia, then there may still be hope for our species...

So check it out – and feel free to leave comments on BLDGBLOG if you have any reactions or further thoughts, especially if you're a student (or faculty member) at Penn.

There we discuss the changing nature of architectural education: what teaching strategies, points of reference, and technologies (such as robotic assembly and 3D printing) can be used most effectively in the classroom. We go through everything from Mies van der Rohe vs. Toll Brothers to the use of algorithms in architectural design; from LEED certification and green building practice to comic books, Archigram, and the use of narrative fiction in student presentations.

On algorithms, for instance, Mertins remarks that the ongoing controversy over whether or not to use mathematics as a generator of architectural form overlooks the fact that reliance on algorithms is simply part of a long "tradition of architects seeking to learn from nature’s capacity to produce forms, patterns and structures of extraordinary beauty and functional prowess. Algorithmic design taps into a giant reservoir of mathematical models already at work in the processes that constitute the universe. In that respect, it’s still a form of mimesis."

It's a good interview, if I do say so myself. For me, as well, it comes with the well-timed realization that if someone as intelligent, articulate, patiently deliberative, and simply good humored as Detlef Mertins can survive the city of Philadelphia, then there may still be hope for our species...

So check it out – and feel free to leave comments on BLDGBLOG if you have any reactions or further thoughts, especially if you're a student (or faculty member) at Penn.

Monday, September 11, 2006

Monday, Monday

My weekly page update:

Garden of Planes in Richmond, Virgina by Gregg Bleam Landscape Architect.

The updated book feature is Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things, by William McDonough and Michael Braungart.

Some unrelated links for your enjoyment:

Garden of Planes in Richmond, Virgina by Gregg Bleam Landscape Architect.

The updated book feature is Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things, by William McDonough and Michael Braungart.

Some unrelated links for your enjoyment:

Langen Foundation

Ando's new building in Neuss, Germany covered at arcspace.com.

At Ground Zero, Towers for Forgetting

Ouroussoff's coverage of the three new towers at the WTC site, on the five year anniversary of September 11.

Vision Not Accomplished

More criticism of the towers at The Slatin Report

Sunday, September 10, 2006

Today's archidose #28

Denver Civic Center Masterplan by c.boschen

Daniel Libeskind's proposal for a revamped Civic Center Park in Denver, Colorado.

To contribute your Flickr images for consideration, just:

:: Join and add photos to the archidose pool, and/or

:: Tag your photos archidose

Friday, September 8, 2006

Three's a Crowd

One consequence of being immersed in a full-time Master's program is that news doesn't reach me as quickly as just a few weeks ago. Last night my wife mentioned that three towers were unveiled as part of Libeskind's masterplan at Ground Zero, but it wasn't until checking my e-mail this afternoon after classes that I saw a rendering at World Architecture News, below.

With SOM's Freedom Tower on the far left, the three new designs from left to right are by Norman Foster, Richard Rogers, and Fumihiko Maki. Based on Libeskind's winning masterplan it appears that only Foster stayed true to the sloping top that gestures towards the voids of the Twin Towers and the memorial below. This a bit unfortunate, though Libeskind is quoted in the New York Times (which includes a slide show of the designs) as saying, "The silhouette of the buildings does exactly what the master plan called for." He goes on to say that the buildings should not look the same, something that appears to be the case in their forms but not necessarily their wrappers, where each is some sort of a variation on a glass box, the prevailing trend in just about every tall building these days.

Foster's building, more than fitting the winning masterplan, also -- unlike the others, at least at first glance -- appears to fit its site, at the NE corner of the greater masterplan site. Its sloping, diamond top recalls the Smurfit-Stone Building in Chicago, sited at the NW corner of Millennium Park. Previously the Stone Container Building, it has received much criticism for its stubbiness, flat detailing, and lack of elegance, but its diamond & sloped top acts as a perfect fulcrum from the buildings to the south along Michigan Avenue and the to the east on Randolph Avenue, and vice-versa. Here, Foster's design acts as the corner fulcrum not only horizontally but also vertically, as it sits between the lower Maki and Rogers designs and the tallest by SOM.

With SOM's Freedom Tower on the far left, the three new designs from left to right are by Norman Foster, Richard Rogers, and Fumihiko Maki. Based on Libeskind's winning masterplan it appears that only Foster stayed true to the sloping top that gestures towards the voids of the Twin Towers and the memorial below. This a bit unfortunate, though Libeskind is quoted in the New York Times (which includes a slide show of the designs) as saying, "The silhouette of the buildings does exactly what the master plan called for." He goes on to say that the buildings should not look the same, something that appears to be the case in their forms but not necessarily their wrappers, where each is some sort of a variation on a glass box, the prevailing trend in just about every tall building these days.

Foster's building, more than fitting the winning masterplan, also -- unlike the others, at least at first glance -- appears to fit its site, at the NE corner of the greater masterplan site. Its sloping, diamond top recalls the Smurfit-Stone Building in Chicago, sited at the NW corner of Millennium Park. Previously the Stone Container Building, it has received much criticism for its stubbiness, flat detailing, and lack of elegance, but its diamond & sloped top acts as a perfect fulcrum from the buildings to the south along Michigan Avenue and the to the east on Randolph Avenue, and vice-versa. Here, Foster's design acts as the corner fulcrum not only horizontally but also vertically, as it sits between the lower Maki and Rogers designs and the tallest by SOM.

Signals of salvation

The answer to your prayers is just a phonecall away: "After Hurricane Jeanne destroyed their steeple, members of the Crossroads Community Church didn't know where they would find the money to replace it. So they prayed for an answer. But they never expected it would come in the form of a cell phone tower. Businessman Paul Scott, who specializes in building disguised or 'stealth' cellphone towers, approached leaders of the church last year with the idea of building a 120-foot-tall tower in the form of a blue-gray metal cross. Concealed inside the top portion of the main pole would be antennas used by Sprint, Nextel and Metro PCS."

(Thanks, Steve! Elsewhere: Pruned explores cellular infrastructure).

(Thanks, Steve! Elsewhere: Pruned explores cellular infrastructure).

Thursday, September 7, 2006

Science Fiction and the City: An Interview with Jeff VanderMeer

The novels of Jeff VanderMeer fall somewhere between science fiction, urban surrealism, dark fantasy, magical realism, and even horror comedy. VanderMeer's literary range becomes immediately apparent when you consider that he's been "a two-time winner (six-time finalist) of the World Fantasy Award, as well as a past finalist for the Hugo Award, the Philip K. Dick Award, the International Horror Guild Award, the British Fantasy Award, the Bram Stoker Award, and the Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award."

[Image: Jeff VanderMeer's City of Saints & Madmen and Shriek: An Afterword. See Shriek's official website].

[Image: Jeff VanderMeer's City of Saints & Madmen and Shriek: An Afterword. See Shriek's official website].

Among others, VanderMeer's books include Veniss Underground, City of Saints & Madmen, and Shriek: An Afterword – the latter published in hardcover just last month. Author news, textual excerpts, MP3s, and imagery from Shriek are all available on that novel's official website. Meanwhile, along with Mark Roberts, VanderMeer is also editor of The Thackery T. Lambshead Pocket Guide to Eccentric & Discredited Diseases, which includes work by dozens of contributors, from Neil Gaiman and Cory Doctorow to China Miéville and K.J. Bishop (official website here).

In light of my own conviction that many of today's most original, historically unencumbered, and frankly exciting architectural ideas are to be found within videogames, films, and science fiction novels, I decided to talk to VanderMeer about his own inventive and novelistic use of the built environment. From his fungal city of Ambergris to the uniquely dark, medicalized underworld of Veniss, VanderMeer's vision is architectural in the broadest – and best – sense.

In the following interview we discuss English cathedrals, "fungal technologies" and architectural infections, the Sydney opera house, Vladimir Nabokov, "The Library of Babel," Monsanto, giant squids and geological deposits, nighttime walks through Prague, and even urban security after the attacks of 9/11.

• • •

BLDGBLOG: To start with the most general question first: if architects, urban planners, and even film makers all look for something in a city – a certain quality to the space, a light, a texture, a density – what do you, as a novelist, look for?

Jeff VanderMeer: Every time I go to a new place, obviously it’s an inspiration of some kind – even if it’s the most awful place in the universe. Like, say, Blackpool, England. I think that when I go to a city I actually do look at texture, because texture is very important in the way I layer my writing. When I go to a city – it’s pretty basic: I literally start on the micro-level. I actually run my hand down the wall to get a sense of what things are like. [laughs] A great example, I think, is when we were in Sydney, and you see the opera house from afar and it’s kind of like this fairy tale creation – it looks so light – but then you get up close and it’s basically just a 1970s piece of concrete, with a very rough and kind of forbidding texture. It’s not what it appears from afar; it’s very much an illusion.

So I think when you get to the actual texture of things – when you actually get a chance to touch the stuff – you get a sense of what it’s actually about. That’s why I like traveling – because I think it’s very important, even when you’re writing a fantasy city, to base it on something real, some first-hand experience. I don’t like the idea that the basic core of what you’re writing about is somehow a reaction to another piece of fiction. I want it to be tactile. I want it to be something concrete, based on something in the real world, that you can extrapolate from. Then maybe you layer in some allusions or influences from other fictions – if it’s applicable in some way, if it adds some kind of resonance.

There’s not really a method beyond that; it’s just what strikes me. Like going to the York Minster, in England – which blew me away and inspired the cadaver cathedral in Veniss Underground. Standing inside that building, which was so absolutely amazing, like nothing I had ever seen before – because I had never had a chance to go inside an old cathedral – how alien it looked and how ethereal and yet so solid – and I literally just stood there looking at it, looking at the inside, looking at the ceiling, for more than an hour.

Being in there, and having been stalled on Veniss, that structure – that piece of architecture – saved my novel. I suddenly understood how to transform something from the real world into something imaginary.

[Image: Interior view of the York Minster. VanderMeer: "Where the sculptures of saints would have been set into the walls, there were instead bodies laid into clear capsules, the white, white skin glistening in the light – row upon row of bodies in the walls, the proliferation of walls. The columns, which rose and arched in bunches of five or six together, were not true columns, but instead highways for blood and other substances: giant red, green, blue, and clear tubes that coursed through the cathedral like arteries. Above, shot through with track lighting from behind, what at first resembled stained-glass windows showing some abstract scene were revealed as clear glass within which organs had been stored: yellow livers, red hearts, pale arms, white eyeballs, rosaries of nerves disembodied from their host." From Veniss Underground]

[Image: Interior view of the York Minster. VanderMeer: "Where the sculptures of saints would have been set into the walls, there were instead bodies laid into clear capsules, the white, white skin glistening in the light – row upon row of bodies in the walls, the proliferation of walls. The columns, which rose and arched in bunches of five or six together, were not true columns, but instead highways for blood and other substances: giant red, green, blue, and clear tubes that coursed through the cathedral like arteries. Above, shot through with track lighting from behind, what at first resembled stained-glass windows showing some abstract scene were revealed as clear glass within which organs had been stored: yellow livers, red hearts, pale arms, white eyeballs, rosaries of nerves disembodied from their host." From Veniss Underground]

BLDGBLOG: How do you achieve – or hope to achieve – believability in an urban setting, giving readers something that (they think) might actually exist?

VanderMeer: As a novelist who is uninterested in replicating “reality” but who is interested in plausibility and verisimilitude, I look for the organizing principles of real cities and for the kinds of bizarre juxtapositions that occur within them. Then I take what I need to be consistent with whatever fantastical city I’m creating. For example, there is a layering effect in many great cities. You don’t just see one style or period of architecture. You might also see planning in one section of a city and utter chaos in another. The lesson behind seeing a modern skyscraper next to a 17th-century cathedral is one that many fabulists do not internalize and, as a result, their settings are too homogenous.

Of course, that kind of layering will work for some readers – and other readers will want continuity. Even if they live in a place like that – a baroque, layered, very busy, confused place – even if, say, they’re holding the novel as they walk down the street in London [laughter] – they just don’t get it. So you have to be careful how you do that. In the novel I’m working on now, I’ll be able to do much more layering because much more time will have passed. It’s set 500 or 1000 years after the events in City of Saints and Shriek. Though I don’t actually refer to specific architectural styles, or to a kind of macro-vision of buildings in the Ambergris universe; I just allude to things.

I also absorb a lot of research. Byzantine art and history. Venetian history. Roman. Etruscan. Indian. Southeast Asian. English. And some of the research was just seeing all of these amazing structures as a child. I mean, you see something like Machu Picchu when you’re eight and it sticks with you! But one thing I find interesting is what people choose to believe and not believe. In the early history of Ambergris, from City of Saints – which does actually have some architectural allusions – the more fantastical stuff is actually taken from Byzantine and other periods. A lot of stuff that’s true to life, people, in emails, will say how cool it is that I made that up. So you never know how someone will react to this stuff.

[Image: John Coulthart, for Jeff VanderMeer's City of Saints & Madmen].

[Image: John Coulthart, for Jeff VanderMeer's City of Saints & Madmen].

BLDGBLOG: Do you actually draw, or map out, the cities and landscapes you describe?

VanderMeer: I do re-draw the city on occasion – and that’s why there’s no map. I don’t want to realize, writing a story later, that, oh, I can’t do that… But I do have a small, simple map – I would just never put it in a book. It’s more so that I can have a general idea of where things are.

The last time we went to New York, a friend of ours was talking about how quickly the neighborhoods change there. Things shift. An area that was a bunch of warehouses can suddenly be a new art district – and I also think of the city of Ambergris as shifting in that way. Neighborhoods will go fallow – almost like, in rural areas, how a field will go fallow – and then it comes back as something else.

I don’t like having too complete a map.

BLDGBLOG: That idea – that a whole neighborhood could go fallow – was actually the premise of an architectural project by a London firm called The Agents of Change. They came up with this almost science fictional scenario, saying: what would happen if Monsanto, or some other multinational genetic-engineering firm, bought the entirety of east London…? So they drew up this whole plan with rooftop gardens and streets turned into croplands – in other words, London itself gone fallow. What’s particularly interesting, though, is that they used a kind of novelistic device or fictional plot to stimulate their architectural design; it's like where creative writing and urban planning intersect. In any case, speculative urban design seems to be a burgeoning literary genre in its own right, from Italo Calvino to China Miéville, or even Franz Kafka and H.G. Wells – or Plato’s Atlantis, for that matter. Thomas More's Utopia. Are there any specific authors in that regard who have influenced your work?

VanderMeer: I get my inspiration from real life as much as possible, and then from history books and then from other writers. I find Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, for example, stultifyingly boring because of this idea of speculative urban design. Although I like the idea of a setting also being a character, it has to also be a character – not be the only thing in the book.

Sometimes I will use authors as something to react against – and say, well, okay: this is an interesting design for a city and this is an interesting design for a city, but neither of these actually work. By kind of cross-correlating them and looking at the differences I can figure out where it is that I want to go.

There have been definite examples where I feel like the city in question, in a piece of fiction, is not connected to anything real – and it’s almost like what happens in bad characterization. In bad characterization, you can’t really imagine anything happening to the character outside the pages of the book. There are cities in fantastical fiction that work the same way, where the writer has obviously put a lot of care into creating the city but it’s somehow inert. It’s simply there as a place for the author to set a story. I think the best cityscapes are kind of like characters. They’re slightly illogical. There’s much more to them than is described in the book. There’s all this stuff that you don’t know – and can’t possibly know.

The Mervyn Peake books, of course – Gormenghast – were pretty influential in terms of setting as character and the idea that a place can create a certain fatalism in the people who live there. That’s the way it is in a real city. In a real city you are, in some ways, reduced to one of many, many stories. And that’s something I think the Ambergris books try to convey: people are shaped, molded, and even overwhelmed by the location they’ve chosen to live in.

[Image: Gormenghast castle; from the BBC miniseries].

[Image: Gormenghast castle; from the BBC miniseries].

BLDGBLOG: What about Borges? There’s a “Borges Bookstore” in City of Saints, for instance – and his “Library of Babel” seems like a story you’d love.

VanderMeer: Borges, for some reason, always leads me to Ballard – at least how they both manipulate time and space in a way that messes with your head. But I think Nabokov is probably a bigger influence – although he and Borges are oddly similar, because they’re kind of like the godfathers of postmodernism. I think a lot of times, when people think they’re seeing Borges’s influence, they’re actually seeing Nabokov’s. But I don’t really like to be pinned down to one thing.

Again, first-hand experience – it seems, after every major trip, that I come back with just notebooks full of ideas, and sketches. And, it’s funny, because it really is a lot of buildings inspiring emotion, which is not something I’d really thought about till now. But it’s true. The contrasts of Bucharest, for instance, really affected me. There are parts of the city that look like Paris and parts that still bear the scars of Communist rule: these inhuman concrete blocks of apartments that look like they're falling apart – and all of this around a very vital and energized populace that was unfailingly friendly. It looked like a city in complete transition, like you could find all possible things there, in both a good and a bad sense. And that impacts heavily on the more industrialized Ambergris of the future that I'm slowly working on now.

But before, when I said I don’t really map things out – I don’t – but every once in a while I will have to sketch a building if I don’t have a good sense for where each character is in the place, or what the place actually looks like. Sometimes I’ll get friends of mine who are artists and are much better at that – I’ll give them a description and they’ll come up with something – and then I’ll be able to visualize it better.

[Image: A digital rendering of Borges's Library of Babel].

[Image: A digital rendering of Borges's Library of Babel].

BLDGBLOG: What non-architectural, or even non-human, spaces or structures have been influential? Reefs, mushrooms, geologic deposits, giant squids, manta rays…?

VanderMeer: That’s an excellent question. The forms of fungus. The wonderful streamlined beauty of a manta ray – these types of things come into play constantly in my fiction. They are constant influences on the cities I describe, especially Ambergris.

We don’t really see the beautiful, alien quality of the world in which we live. And it is the shapes and structures of this beauty that appeal to me. I mean, people laugh when I talk about squid, but, my god, what an amazing creature! What an amazing form! Geological deposits as well. And I sometimes feel as if there’s almost a linkage of form between all of these things that draws me to them.

My earliest memories are of Fiji, a volcanic atoll, where the reefs are just offshore. Our school was right near one of these reefs – and I remember, from like the age of six to ten, we would just walk out there, you know, at recess… And, in a sense, I feel like some of the Veniss Underground stuff was an inversion of that. There were so many crevices and hiding places and bizarre things sort of hidden in the reef. Sometimes my dad and mom would take us out there at night – which was amazing, because of the bioluminescence from a lot of the different creatures out there, including the squid. There was a sense of encountering something totally alien.

I just think this stuff is absolutely beautiful, and alien, and – in many cases – kind of horrific. You read about fungus, and there are certain types of fruiting bodies or mushrooms that you can feed different things. Like one of the strangest things in "King Squid," I think, is a scene where the father of the narrator creates a mushroom that is mostly made of iron filings – because that’s what he feeds it: ground up little bits of iron. And that’s actually true. A mushroom actually will absorb these types of things. You can make a mushroom that is mostly made of iron. [laughs] I assume it dies relatively soon thereafter. [laughter]

The world is a very strange place. We shouldn’t take that for granted. That’s why I highlight some of this stuff, and write about it – because it’s just so fantastic.

BLDGBLOG: Fantastic – but also vaguely threatening in a way?

VanderMeer: I don’t see it as threatening. It’s just the context in which the character encounters it that makes it a hazard, or a threat. I think that confluences of the inorganic and the organic feel threatening to people for some primal reason that I can’t quite put a finger to.

[Image: John Coulthart, for Jeff VanderMeer's City of Saints & Madmen].

[Image: John Coulthart, for Jeff VanderMeer's City of Saints & Madmen].

BLDGBLOG: In City of Saints you describe fungi – specifically, lichen – as a kind of living architectural ornament. You write how “much of the ‘gold’ covering the buildings was actually a living organism similar to lichen that the gray caps had trained to create decorative patterns.” Elsewhere in the book, those lichen “covered the walls in intricate patterns, crossed through with a royal red fungus that formed star shapes.” What do these examples imply about the possibilities for entire living cities, or even a reef-like architecture made entirely from organisms? What about architectural infections, or diseases and infestations that would act to enhance a manmade space?

VanderMeer: Scientists have already created buildings that are self-cleaning using certain types of bacteria, I believe. So this is as much a “science fictional” idea as a fantastical one, that’s for sure. I’m all about extrapolating fungal technologies. It creates an extra frisson of satisfaction in the reader, for one thing.

Something I’m working toward in the next Ambergris novels is this idea of how architecture and the organic interact. In fact, in the new novel, Shriek, there’s a whole passage devoted to this. At one point, the narrator comes to realize that there’s an entirely other city under the skin of what she can see – because her brother has constructed these glasses that kind of allow you to see with a sense that human beings don’t actually have. And what she sees is that every single building is just coated with fungus, invisible to the naked eye, and with living things forming separate symbols and signs. It’s on every wall that she looks at. It’s like a fungal architecture imposed on top of the city.

BLDGBLOG: Or urbanism in an age of microbacteria – when every surface is just covered with a film of germs and infectious organisms.

VanderMeer: I thought about that, too. There actually is all this micro-bacterial activity – things we can’t see – so it’s not too different from reality. And infections! Infections are so primal, symbolic, integral – whether infections of ideas or infections of the physical. In Ambergris, fungal infections are not just a physical thing but the physical manifestation of a deep psychic wound in the citizenry – a mixed guilt and dread.

I think infection is dealt with rather badly in current literature. You almost have to go back to the Decadents – to before we had vaccines and things of that nature – to see exploration of this theme in an interesting way. But I love the idea of mixing physical and mental infections. We all suffer from mental infections. So what if you breathe in a spore and you suddenly are infected with an idea? (Again, from a forthcoming book.)

[Image: From Charting Nature].

[Image: From Charting Nature].

BLDGBLOG: I’m curious if your enthusiasm for all things fungal comes from living in Florida?

VanderMeer: I think Florida creeps up on you in terms of the fungal. It’s there, but you don’t at first recognize it. You don’t recognize it because of the slow pace of life in subtropical climates. So you are lulled into forgetting about decay, and yet even though there is a slowness, or perceived slowness, because of the heat, etc., there is a ferocious and pitiless war of decay occurring at the same time – of decomposition. And it’s an awareness of this that helps fuel my fiction – the juxtaposition of these ideas and the kind of pathos of it, how it mimics the limited span of life.

BLDGBLOG: I'm also curious if the more densely knit and pedestrianized urban cores of cities you recently traveled through – like Prague – impressed you with their capacity for turning even a simple walk into an event, full of intrigue and coincidence – or if it just made you claustrophobic, longing for the massive, inhuman highways of the United States?

VanderMeer: Honestly, I don't understand how we in the U.S. even have a sense of community, except in those cities that allow for a neighborhood bar and a neighborhood grocery store and the kind of walkability that you find in most European cities. We loved the walkability and playfulness of Prague. Prague was the city that, in its entirety, had the sense of mystery and puckishness and slight danger closest to Ambergris of any place we visited. We loved that sense of adventure and exploration in Prague. We loved that around any given street corner we might find a musician or a band or an art exhibit or a movie being shot. It seemed like a city completely alive with culture, to the point of being ruled by it.

That first night in Prague, where you'd spill out from some crooked, tiny medieval street into a courtyard full of light and clocktowers and people... that was pretty amazing.

[Image: Prague, photographed by Karel Plicka; via John Coulthart's Feuilleton].

[Image: Prague, photographed by Karel Plicka; via John Coulthart's Feuilleton].

BLDGBLOG: Finally, in Veniss, you describe how the “aboveground levels” of the city are “so divided into different governments that a trip from one end of the city to the other requires eighteen security stops.” In City of Saints, an ancient city called “Cinsorium” – a pun on both sin and sensorium – is razed, replaced by a city called “Sophia” – wisdom, reason. Below Ambergris are the gray caps, hallucinogenic mushroom-natives who kidnap unwary surface dwellers. Elsewhere, Tonsure encounters a city seemingly modeled after one of Terence McKenna's most extreme, drug-induced visions – a kind of psilocybin urbanism. So you’ve got post-9/11 politics, the War on Drugs, class division, allegorical commentary on the triumph of reason over the senses and the flesh – all of these topics seem encoded into your fictive descriptions of urban space. Could you talk a bit about how you use cities – or architecture in general – to communicate an implicit message, whether that’s socio-political, religious, or simply poetic?

VanderMeer: Well, it’s kind of as you describe – I let whatever’s happening in the world wash over me and into the urban space. I think the mistake in trying to incorporate 9/11, for example, into fiction is in having it be something characters talk about. It’s more about just hard-wiring stuff like that into the culture and cityscapes so it becomes something larger than the characters, that’s just part of the backdrop. I find that almost anything that comes along is fodder for Ambergris, for example. It can absorb just about anything, like a good city should.

But as for how I consciously do it, I couldn’t tell you. I am agnostic, cynical about capitalism and communism, and all for individuals over institutions, while recognizing that central government is necessary to provide social services, etc.

I’m sure that’s reflected in the cities I create.

[Image: John Coulthart, for Jeff VanderMeer's City of Saints & Madmen].

[Image: John Coulthart, for Jeff VanderMeer's City of Saints & Madmen].

• • •

You can read more about Jeff VanderMeer at his blog, VanderWorld – where you'll also find news about his forthcoming books and Shriek: The Movie.

[With thanks to John Coulthart for the use of his extraordinary images (don't miss Coulthart's other work); to Neddal Ayad for helping me contact VanderMeer in the first place; and to Jeff VanderMeer himself, who energetically saw this interview through to completion].

Among others, VanderMeer's books include Veniss Underground, City of Saints & Madmen, and Shriek: An Afterword – the latter published in hardcover just last month. Author news, textual excerpts, MP3s, and imagery from Shriek are all available on that novel's official website. Meanwhile, along with Mark Roberts, VanderMeer is also editor of The Thackery T. Lambshead Pocket Guide to Eccentric & Discredited Diseases, which includes work by dozens of contributors, from Neil Gaiman and Cory Doctorow to China Miéville and K.J. Bishop (official website here).

In light of my own conviction that many of today's most original, historically unencumbered, and frankly exciting architectural ideas are to be found within videogames, films, and science fiction novels, I decided to talk to VanderMeer about his own inventive and novelistic use of the built environment. From his fungal city of Ambergris to the uniquely dark, medicalized underworld of Veniss, VanderMeer's vision is architectural in the broadest – and best – sense.

In the following interview we discuss English cathedrals, "fungal technologies" and architectural infections, the Sydney opera house, Vladimir Nabokov, "The Library of Babel," Monsanto, giant squids and geological deposits, nighttime walks through Prague, and even urban security after the attacks of 9/11.

BLDGBLOG: To start with the most general question first: if architects, urban planners, and even film makers all look for something in a city – a certain quality to the space, a light, a texture, a density – what do you, as a novelist, look for?

Jeff VanderMeer: Every time I go to a new place, obviously it’s an inspiration of some kind – even if it’s the most awful place in the universe. Like, say, Blackpool, England. I think that when I go to a city I actually do look at texture, because texture is very important in the way I layer my writing. When I go to a city – it’s pretty basic: I literally start on the micro-level. I actually run my hand down the wall to get a sense of what things are like. [laughs] A great example, I think, is when we were in Sydney, and you see the opera house from afar and it’s kind of like this fairy tale creation – it looks so light – but then you get up close and it’s basically just a 1970s piece of concrete, with a very rough and kind of forbidding texture. It’s not what it appears from afar; it’s very much an illusion.

So I think when you get to the actual texture of things – when you actually get a chance to touch the stuff – you get a sense of what it’s actually about. That’s why I like traveling – because I think it’s very important, even when you’re writing a fantasy city, to base it on something real, some first-hand experience. I don’t like the idea that the basic core of what you’re writing about is somehow a reaction to another piece of fiction. I want it to be tactile. I want it to be something concrete, based on something in the real world, that you can extrapolate from. Then maybe you layer in some allusions or influences from other fictions – if it’s applicable in some way, if it adds some kind of resonance.

There’s not really a method beyond that; it’s just what strikes me. Like going to the York Minster, in England – which blew me away and inspired the cadaver cathedral in Veniss Underground. Standing inside that building, which was so absolutely amazing, like nothing I had ever seen before – because I had never had a chance to go inside an old cathedral – how alien it looked and how ethereal and yet so solid – and I literally just stood there looking at it, looking at the inside, looking at the ceiling, for more than an hour.

Being in there, and having been stalled on Veniss, that structure – that piece of architecture – saved my novel. I suddenly understood how to transform something from the real world into something imaginary.

BLDGBLOG: How do you achieve – or hope to achieve – believability in an urban setting, giving readers something that (they think) might actually exist?

VanderMeer: As a novelist who is uninterested in replicating “reality” but who is interested in plausibility and verisimilitude, I look for the organizing principles of real cities and for the kinds of bizarre juxtapositions that occur within them. Then I take what I need to be consistent with whatever fantastical city I’m creating. For example, there is a layering effect in many great cities. You don’t just see one style or period of architecture. You might also see planning in one section of a city and utter chaos in another. The lesson behind seeing a modern skyscraper next to a 17th-century cathedral is one that many fabulists do not internalize and, as a result, their settings are too homogenous.

Of course, that kind of layering will work for some readers – and other readers will want continuity. Even if they live in a place like that – a baroque, layered, very busy, confused place – even if, say, they’re holding the novel as they walk down the street in London [laughter] – they just don’t get it. So you have to be careful how you do that. In the novel I’m working on now, I’ll be able to do much more layering because much more time will have passed. It’s set 500 or 1000 years after the events in City of Saints and Shriek. Though I don’t actually refer to specific architectural styles, or to a kind of macro-vision of buildings in the Ambergris universe; I just allude to things.

I also absorb a lot of research. Byzantine art and history. Venetian history. Roman. Etruscan. Indian. Southeast Asian. English. And some of the research was just seeing all of these amazing structures as a child. I mean, you see something like Machu Picchu when you’re eight and it sticks with you! But one thing I find interesting is what people choose to believe and not believe. In the early history of Ambergris, from City of Saints – which does actually have some architectural allusions – the more fantastical stuff is actually taken from Byzantine and other periods. A lot of stuff that’s true to life, people, in emails, will say how cool it is that I made that up. So you never know how someone will react to this stuff.

BLDGBLOG: Do you actually draw, or map out, the cities and landscapes you describe?

VanderMeer: I do re-draw the city on occasion – and that’s why there’s no map. I don’t want to realize, writing a story later, that, oh, I can’t do that… But I do have a small, simple map – I would just never put it in a book. It’s more so that I can have a general idea of where things are.

The last time we went to New York, a friend of ours was talking about how quickly the neighborhoods change there. Things shift. An area that was a bunch of warehouses can suddenly be a new art district – and I also think of the city of Ambergris as shifting in that way. Neighborhoods will go fallow – almost like, in rural areas, how a field will go fallow – and then it comes back as something else.

I don’t like having too complete a map.

BLDGBLOG: That idea – that a whole neighborhood could go fallow – was actually the premise of an architectural project by a London firm called The Agents of Change. They came up with this almost science fictional scenario, saying: what would happen if Monsanto, or some other multinational genetic-engineering firm, bought the entirety of east London…? So they drew up this whole plan with rooftop gardens and streets turned into croplands – in other words, London itself gone fallow. What’s particularly interesting, though, is that they used a kind of novelistic device or fictional plot to stimulate their architectural design; it's like where creative writing and urban planning intersect. In any case, speculative urban design seems to be a burgeoning literary genre in its own right, from Italo Calvino to China Miéville, or even Franz Kafka and H.G. Wells – or Plato’s Atlantis, for that matter. Thomas More's Utopia. Are there any specific authors in that regard who have influenced your work?

VanderMeer: I get my inspiration from real life as much as possible, and then from history books and then from other writers. I find Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, for example, stultifyingly boring because of this idea of speculative urban design. Although I like the idea of a setting also being a character, it has to also be a character – not be the only thing in the book.

Sometimes I will use authors as something to react against – and say, well, okay: this is an interesting design for a city and this is an interesting design for a city, but neither of these actually work. By kind of cross-correlating them and looking at the differences I can figure out where it is that I want to go.

There have been definite examples where I feel like the city in question, in a piece of fiction, is not connected to anything real – and it’s almost like what happens in bad characterization. In bad characterization, you can’t really imagine anything happening to the character outside the pages of the book. There are cities in fantastical fiction that work the same way, where the writer has obviously put a lot of care into creating the city but it’s somehow inert. It’s simply there as a place for the author to set a story. I think the best cityscapes are kind of like characters. They’re slightly illogical. There’s much more to them than is described in the book. There’s all this stuff that you don’t know – and can’t possibly know.

The Mervyn Peake books, of course – Gormenghast – were pretty influential in terms of setting as character and the idea that a place can create a certain fatalism in the people who live there. That’s the way it is in a real city. In a real city you are, in some ways, reduced to one of many, many stories. And that’s something I think the Ambergris books try to convey: people are shaped, molded, and even overwhelmed by the location they’ve chosen to live in.

[Image: Gormenghast castle; from the BBC miniseries].

[Image: Gormenghast castle; from the BBC miniseries].BLDGBLOG: What about Borges? There’s a “Borges Bookstore” in City of Saints, for instance – and his “Library of Babel” seems like a story you’d love.

VanderMeer: Borges, for some reason, always leads me to Ballard – at least how they both manipulate time and space in a way that messes with your head. But I think Nabokov is probably a bigger influence – although he and Borges are oddly similar, because they’re kind of like the godfathers of postmodernism. I think a lot of times, when people think they’re seeing Borges’s influence, they’re actually seeing Nabokov’s. But I don’t really like to be pinned down to one thing.