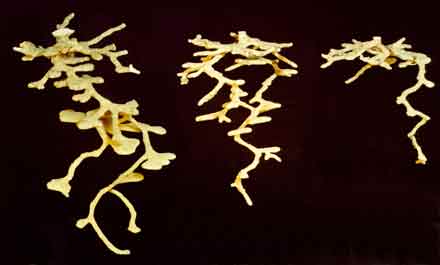

In the Fall of 2001, Cabinet Magazine introduced us to Walter Tschinkel, a professor of entomology at Florida State University. Tschinkel "has been making plaster casts of ant nests since 1982, when he first heard of the strength of orthodontic plaster. The painstaking process involves pouring the plaster down the opening as quickly as it will go in. After the plaster hardens, the excavation begins, but the nest must be taken out piece by piece. (One harvester ant nest, for example, took some five gallons of plaster and came out in 180 pieces.)"

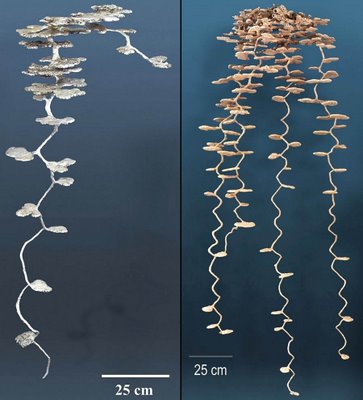

"Sometimes more than ten feet tall, the nests are as beautiful in structure as they are complex."

In a fascinating research paper (available through Florida State University as a PDF), Tschinkel describes subterranean ants' nests as "shaped voids in a soil matrix." These casts, Tschinkel tells us, offer "an invaluable way to visualize ant colonies as they are, that is as a three-dimensional network of tunnels and chambers."

In an even more interesting – not to mention better illustrated – paper (also available as a PDF) Tschinkel takes us on a verbal tour of this buried architecture: "In contrast to shafts," he writes, the chambers all "had more or less horizontal floors and a horizontal outline ranging from near circular when small, to multi-lobed when large. In vertical cross-section, they were flattened or slightly domed, with the horizontal dimension much greater than the vertical. All chambers were about 1 cm high, floor to ceiling, no matter what the floor area. Shafts usually intersected chambers at an edge, and connected sequential chambers. Below about 15 to 20 cm, chambers always began as lateral, horizontal-floored extensions from the outside of a spirally-descending shaft that therefore intersected the inner edge of the chamber at an angle ranging from 25º to about 70º."

The social behavior of the ants is, in many ways, what produces the structures. Tschinkel refers to "movement zones," in which "partially overlapping sequences from the center of the nest to the periphery" are traced and retraced by individual ants. These movements gradually erode at the walls, expanding surfaces into actual rooms. These "spaces," then, are really the physical results of social activity, in which a surface becomes a route becomes a chamber – and further branchings spread outward (or downward) from there. (Substantially more information on this – including the influential role of carbon dioxide – can be found in this PDF).

"Chamber morphology," meanwhile, "was rarely elongated and shaft-like." Rather, each chamber "began as a niche in the outer wall of a shaft." Etc. etc.

The process of making these casts almost always kills the ants in the nests, however; but that is "not something I like doing," Tschinkel says.

Of course, the urge toward revealing invisible architecture can overwhelm even the best...

(Thanks to jpb for the link! And this post is directly related to an earlier post, Wormholes in Wood, which discusses the more conceptual aspects of such a project).

No comments:

Post a Comment