In 1999, Swiss architect Mario Botta was commissioned to design a model of Francesco Borromini’s Church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, in Rome.

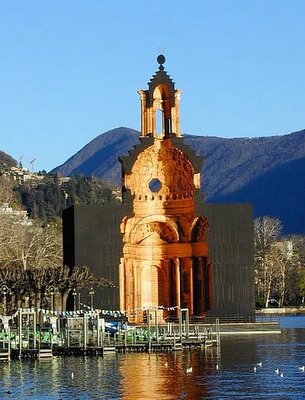

In 1999, Swiss architect Mario Botta was commissioned to design a model of Francesco Borromini’s Church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, in Rome. Called San Carlino, Botta's model – part building, part sculpture – was erected near Borromini's own birthplace, on the shores of Lake Lugano, to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Borromini's birth.

The work was dismantled in 2003.

The project was made using 35,000 wood boards, each of which was cut, milled, and sanded, then assembled with the rest to reproduce the exact internal volume of Borromini's church.

Well, half of Borromini's church.

The interior, in other words, was carved out of this colossus of wood; the space of the church was milled, excavated from the stacked material.

This virtual walk-through gives a nice, if badly lit, sense of the abrupt edge Botta designed for the model –

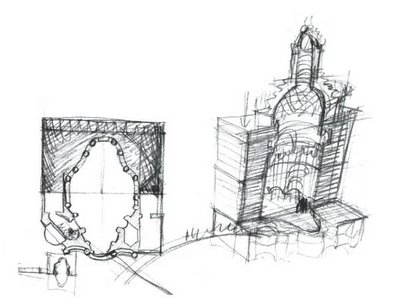

– because as you can see from Botta's own sketch, below, he effectively cut the church in half; measured the internal volume down to the scale of centimeters; then reproduced that void using 35,000 specially cut boards.

Certain photographs I've seen are actually quite astonishing; the freshly cut boards in the earliest photographs all but glow compared to the coal-black exterior, and the blue skies of Lugano add a surreal backdrop to the unexpected sight of the semi-sacred hollow.

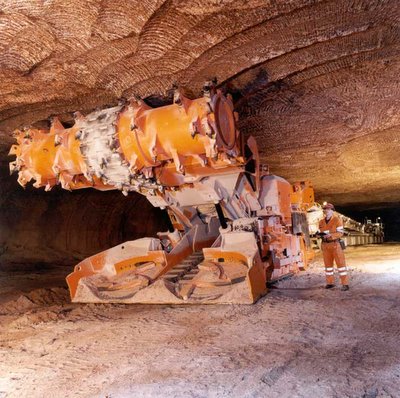

I have to admit, however, that when I first saw those photographs I did not understand what I was looking at. My first reaction was fairly predictable, I suppose, and that was to picture a huge milling-machine, built to the exact volume and measurements of Borromini's church – a kind of void-grinder several stories high, whirring with precise blades and abraders, like some massive (perhaps consecrated) mining machine.

That would, of course, be ridiculous; but it got me thinking.

I wondered if you could precisely measure the interior space of Notre-Dame, for instance, then build or program an industrial-scale grinding machine to those exact specifications. A kind of inside-out abrader. A void-grinder. You could then park that thing in front of a mountain and lo! Three hours later the exact internal dimensions of Notre-Dame – the hollows and side-chapels, the soaring interior of cross-vaults – have been carved, in real size, into the granite surface of the Teton Range.

You can walk into that hollow, light a candle, and be damned if it doesn't look exactly like the real thing...

In fact, you could do this for any cathedral on the planet. Measure its exact interior volume, using lasers perhaps, and then use those measurements to fabricate a grinding-machine. Then choose your target: the interior of Chartres, for instance, could be carved into the quartz-belted strata of the Canadian Rockies. The interior of St. Paul's whirred and abraded into the mountains of Bamiyan, where the Buddhas once stood.

You could even map out, to the millimeter, the internal volume of every cathedral, mosque, and temple in the world, and then program that into a robotic rock-milling machine. You then send that machine to the moon where, over the course of two generations, it carves the exact, to-scale internal voids of beautiful sacred architecture into the lunar surface.

From the earth it looks as if small caves are appearing on the moon, like sink-holes or new craters – but you take out your telescope, walk into the backyard with your friends, look up, and, there, hollowed out, void-black on the moon, are hollow reproductions of Chartres Cathedral, Salisbury, Hagia Sophia, Angkor Wat.

Future lunar expeditions go torchlit through those caves, re-breathing tanked oxygen: what were these things...? What built them...?

No comments:

Post a Comment